Today, PROOF, an interdisciplinary research program investigating household food insecurity in Canada, provides a long-awaited look into the current state of food insecurity in this country.

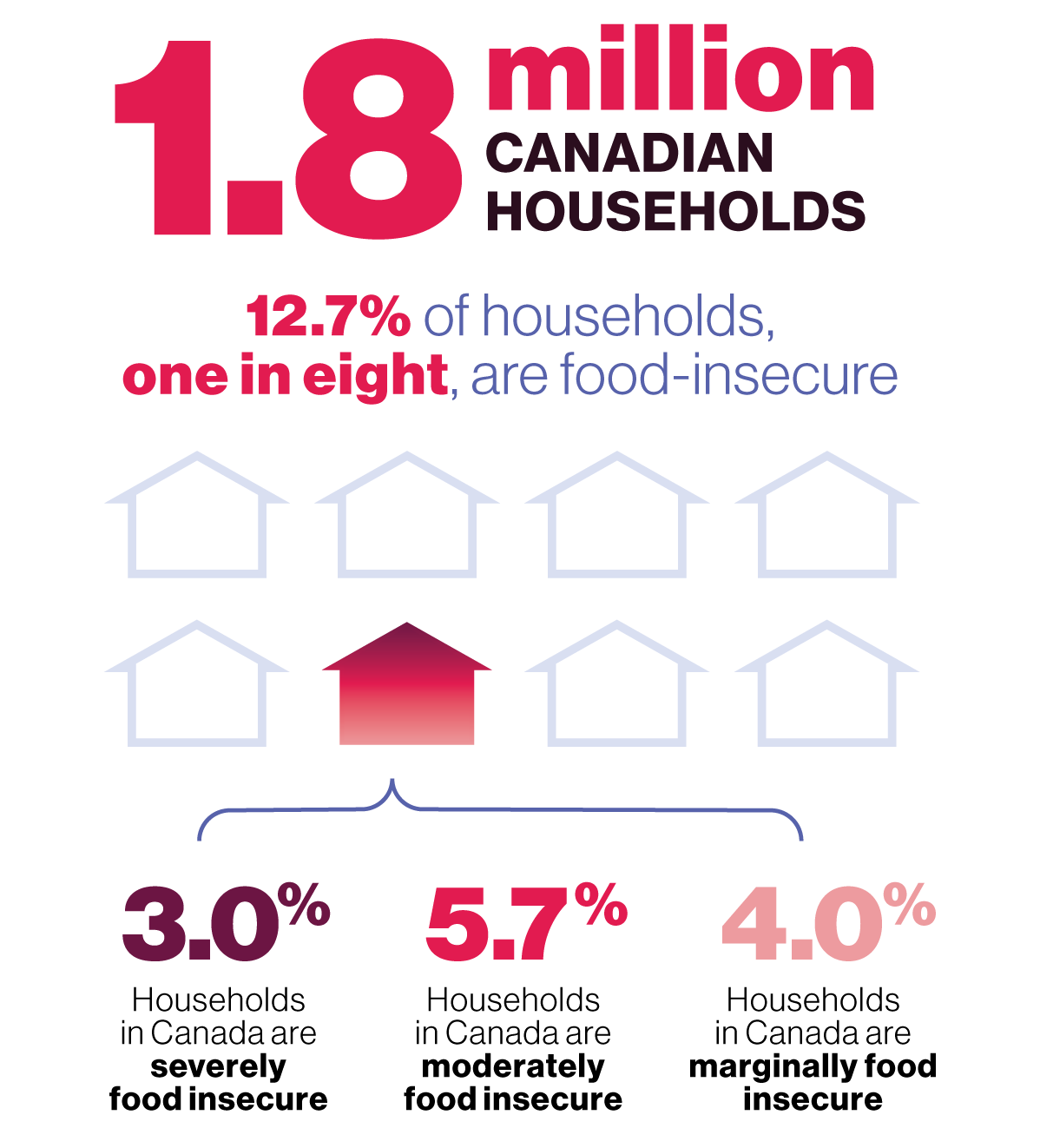

Drawing on data for 103,500 households from Statistics Canada’s 2017-18 Canadian Community Health Survey, we found that 1 in 8 households were food insecure. This represents 4.4 million people, the largest number recorded since Canada began monitoring food insecurity. And this number is an underestimate. The survey sample does not include people living on First Nations reserves, people in some remote northern areas, or people who are homeless – i.e., three groups at high risk of food insecurity.

What is food insecurity?

Household food insecurity refers to the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints. The experiences assessed to determine a household’s ‘food security status’ range from concerns about running out of food before there is more money to buy more, to the inability to afford a balanced diet, to going hungry, missing meals, and in extreme cases, not eating for whole days because of a lack of food and money for food.

Taken at face value, these questions suggest that food insecurity is a food problem – resolvable by programs that provide food for free or make it more accessible and affordable. But this misses the bigger picture. The deprivation experienced by food-insecure households is not limited to food. By the time people are struggling to put food on the table because of a lack of money, they are having trouble meeting all kinds of other expenses. Food-insecure households compromise spending on all kinds of necessities, including housing and prescription medications.

Who is food insecure?

Those most at risk are households with low incomes and limited assets (indicated on this survey by renting rather than owning your housing). Indigenous and Black households are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity, a finding reflective of the potent effects of colonialism and structural racism in Canada.

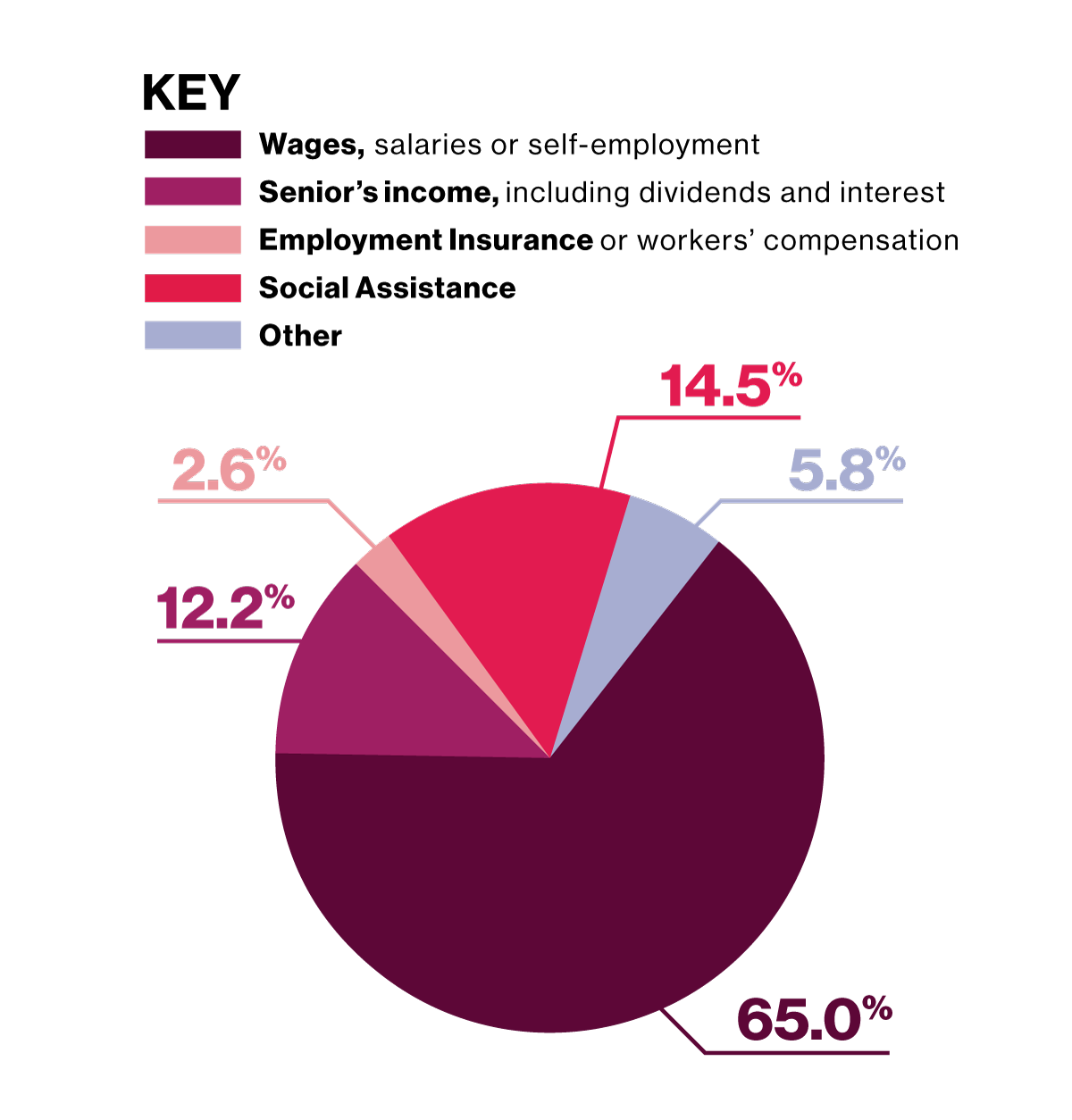

About 60% of households who report their main source of income as social assistance were food insecure. While not new, the finding is a stark reminder of the inadequacy of our ‘income support program of last resort’. Many of those who manage to qualify for income assistance cannot meet their basic needs. Almost one-third of those households reliant on Employment Insurance (EI) or Workers’ Compensation were also food-insecure, raising questions about the adequacy of these supports.

While the risk of food insecurity is greatest for households reliant on social assistance, EI or Workers’ Compensation, it is important to note that two-thirds of the households reported their main source of income as salaries or wages. Food insecurity is a serious problem for working Canadians.

Food-insecure households’ main source of income

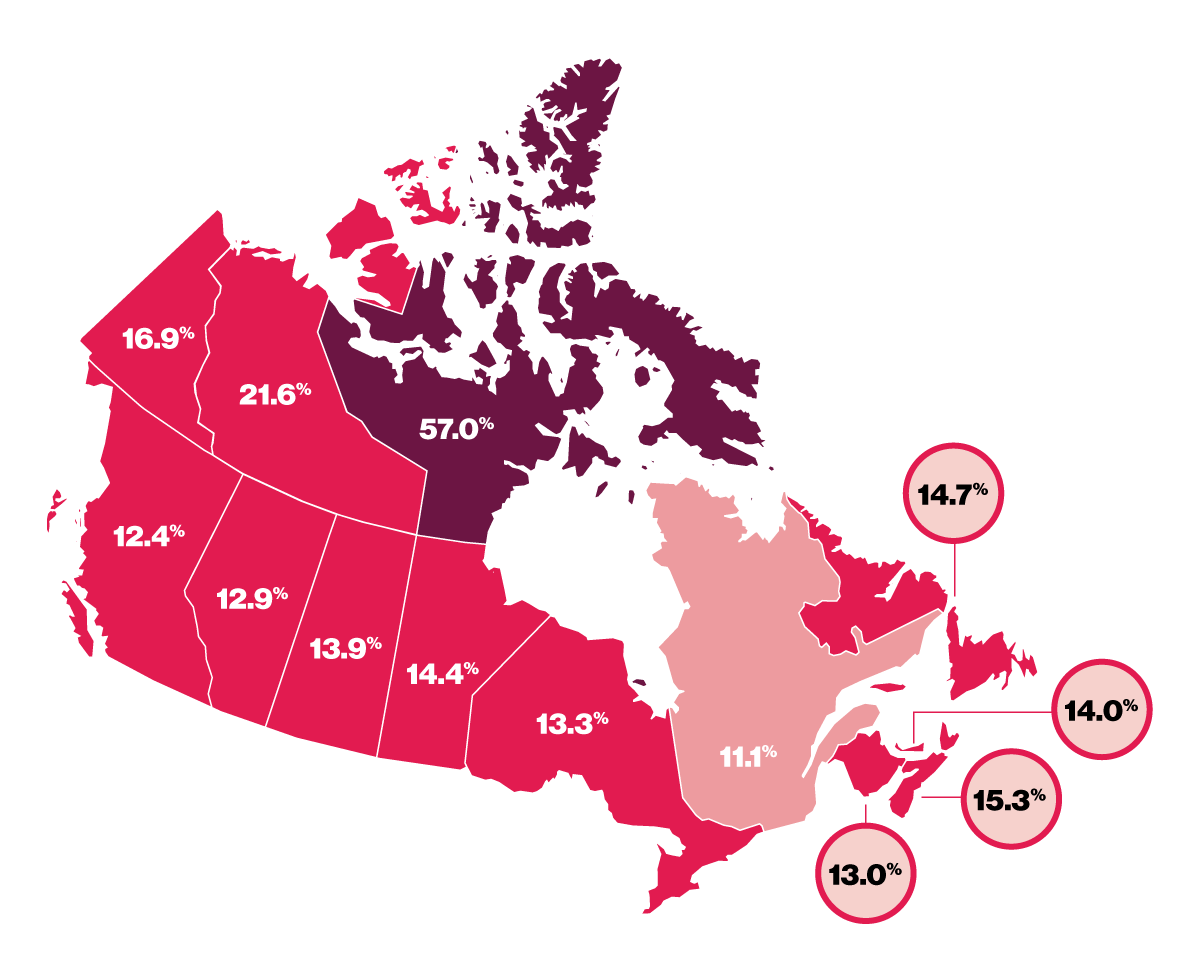

Although 84% of people affected by food insecurity live in either Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, or British Columbia, there are clear geographic disparities in food insecurity rates. Food insecurity is much more prevalent in Nunavut than any other part of Canada. 57% of households in Nunavut reported some level of food insecurity and almost half of these households were severely food insecure (meaning that members experienced absolute food deprivation). The lowest prevalence of household food insecurity was 11% in Quebec. In fact, Quebec was the only place in Canada where the prevalence of food insecurity fell significantly between 2015-16 and 2017-18.

Household Food Insecurity by Province and Territory

Data source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 2017-18.

Food insecurity is more common among households with children than those without. 17% of children under 18, or more than 1 in 6, lived in a family that experienced food insecurity. Across Canada, this rate ranged from a low of 15% in British Columbia to a high of 79% in Nunavut. The families most at risk were those headed by lone-parent women; one-third were food-insecure.

Food insecurity is a health problem.

It matters that 1 in 8 Canadian households were food-insecure in 2017-18 because such deprivation has profound negative effects on people’s health. The research on the relationship between food insecurity and health is unequivocal. Among children, exposure to severe food insecurity has been linked to the subsequent development of a variety of chronic health conditions, including asthma and depression. Adults in food-insecure households have higher rates of a wide variety of chronic diseases, including mental health problems, arthritis, asthma, and diabetes. They are also more likely to die prematurely. By our best estimate, adults in severely food-insecure households in Canada die 9 years sooner than the rest of us.

Because of its toxic effects on health, household food insecurity also places a substantial burden on our health care system.

How can we solve this problem?

-

We must address its root causes – food programs are not the solution.

The persistently high prevalence of household food insecurity across Canada highlights the need for more effective, evidence-based responses. To date, there have been lots of federal, provincial, territorial, and local initiatives to support community food programs, including the federal government’s Local Food Infrastructure Fund launched last year. But food programs can’t fix the problem of household food insecurity that has been documented in this report.

-

Governments must re-evaluate the adequacy of income supports and protections for low-income Canadians.

Tackling the conditions that give rise to food insecurity means re-evaluating the adequacy of the income supports and protections that are currently provided to very low-income, working-aged Canadians and their families. For example, our recent study of the Canada Child Benefit suggests that this new federal benefit reduced severe food insecurity among low-income families with children, but it did not make them food-secure. The high rate of food insecurity among families with children points to a need to review the benefit amounts for low-income families (i.e., those most vulnerable to food insecurity) to ensure that they are adequately supported to meet basic needs. Other federal programs like the Canada Workers Benefit also need to be reviewed to ensure that they are as effective as they can be in protecting low-income Canadians from food insecurity.

-

Governments must design programs and policies in ways that ensure that vulnerable, low-income households have sufficient funds to make ends meet.

While federal leadership is imperative, provincial and territorial governments’ engagement in policies to reduce food insecurity is also critical. Given that the provinces and territories are responsible for health care, they bear the costs of food insecurity insofar as it increases people’s needs for health services. There are clear differences in food insecurity prevalence across the provinces and territories and within some jurisdictions (notably Quebec) over time. The effects of specific provincial/territorial policies on food insecurity rates warrant much more evaluation. What is known suggests that provincial and territorial government actions matter. Many important policy levers rest with the provinces and territories. They are responsible for social assistance, they set minimum wages and employment standards, they deliver social housing programs, they levy taxes and deliver tax credits, and many provide child benefits.

It’s time to recognize food insecurity is a serious public health problem in Canada, a problem that is only getting worse. Without deliberate, evidence-based policy interventions by federal, provincial and territorial governments, this problem will continue to fester.

For more information, see the Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017-18 report

Commentary | Resource | Story

More Canadians are food insecure than ever before – and the problem is only getting worse

March 11, 2020

Today, PROOF, an interdisciplinary research program investigating household food insecurity in Canada, provides a long-awaited look into the current state of food insecurity in this country.

Drawing on data for 103,500 households from Statistics Canada’s 2017-18 Canadian Community Health Survey, we found that 1 in 8 households were food insecure. This represents 4.4 million people, the largest number recorded since Canada began monitoring food insecurity. And this number is an underestimate. The survey sample does not include people living on First Nations reserves, people in some remote northern areas, or people who are homeless – i.e., three groups at high risk of food insecurity.

What is food insecurity?

Household food insecurity refers to the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints. The experiences assessed to determine a household’s ‘food security status’ range from concerns about running out of food before there is more money to buy more, to the inability to afford a balanced diet, to going hungry, missing meals, and in extreme cases, not eating for whole days because of a lack of food and money for food.

Taken at face value, these questions suggest that food insecurity is a food problem – resolvable by programs that provide food for free or make it more accessible and affordable. But this misses the bigger picture. The deprivation experienced by food-insecure households is not limited to food. By the time people are struggling to put food on the table because of a lack of money, they are having trouble meeting all kinds of other expenses. Food-insecure households compromise spending on all kinds of necessities, including housing and prescription medications.

Who is food insecure?

Those most at risk are households with low incomes and limited assets (indicated on this survey by renting rather than owning your housing). Indigenous and Black households are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity, a finding reflective of the potent effects of colonialism and structural racism in Canada.

About 60% of households who report their main source of income as social assistance were food insecure. While not new, the finding is a stark reminder of the inadequacy of our ‘income support program of last resort’. Many of those who manage to qualify for income assistance cannot meet their basic needs. Almost one-third of those households reliant on Employment Insurance (EI) or Workers’ Compensation were also food-insecure, raising questions about the adequacy of these supports.

While the risk of food insecurity is greatest for households reliant on social assistance, EI or Workers’ Compensation, it is important to note that two-thirds of the households reported their main source of income as salaries or wages. Food insecurity is a serious problem for working Canadians.

Food-insecure households’ main source of income

Although 84% of people affected by food insecurity live in either Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, or British Columbia, there are clear geographic disparities in food insecurity rates. Food insecurity is much more prevalent in Nunavut than any other part of Canada. 57% of households in Nunavut reported some level of food insecurity and almost half of these households were severely food insecure (meaning that members experienced absolute food deprivation). The lowest prevalence of household food insecurity was 11% in Quebec. In fact, Quebec was the only place in Canada where the prevalence of food insecurity fell significantly between 2015-16 and 2017-18.

Household Food Insecurity by Province and Territory

Data source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 2017-18.

Food insecurity is more common among households with children than those without. 17% of children under 18, or more than 1 in 6, lived in a family that experienced food insecurity. Across Canada, this rate ranged from a low of 15% in British Columbia to a high of 79% in Nunavut. The families most at risk were those headed by lone-parent women; one-third were food-insecure.

Food insecurity is a health problem.

It matters that 1 in 8 Canadian households were food-insecure in 2017-18 because such deprivation has profound negative effects on people’s health. The research on the relationship between food insecurity and health is unequivocal. Among children, exposure to severe food insecurity has been linked to the subsequent development of a variety of chronic health conditions, including asthma and depression. Adults in food-insecure households have higher rates of a wide variety of chronic diseases, including mental health problems, arthritis, asthma, and diabetes. They are also more likely to die prematurely. By our best estimate, adults in severely food-insecure households in Canada die 9 years sooner than the rest of us.

Because of its toxic effects on health, household food insecurity also places a substantial burden on our health care system.

How can we solve this problem?

We must address its root causes – food programs are not the solution.

The persistently high prevalence of household food insecurity across Canada highlights the need for more effective, evidence-based responses. To date, there have been lots of federal, provincial, territorial, and local initiatives to support community food programs, including the federal government’s Local Food Infrastructure Fund launched last year. But food programs can’t fix the problem of household food insecurity that has been documented in this report.

Governments must re-evaluate the adequacy of income supports and protections for low-income Canadians.

Tackling the conditions that give rise to food insecurity means re-evaluating the adequacy of the income supports and protections that are currently provided to very low-income, working-aged Canadians and their families. For example, our recent study of the Canada Child Benefit suggests that this new federal benefit reduced severe food insecurity among low-income families with children, but it did not make them food-secure. The high rate of food insecurity among families with children points to a need to review the benefit amounts for low-income families (i.e., those most vulnerable to food insecurity) to ensure that they are adequately supported to meet basic needs. Other federal programs like the Canada Workers Benefit also need to be reviewed to ensure that they are as effective as they can be in protecting low-income Canadians from food insecurity.

Governments must design programs and policies in ways that ensure that vulnerable, low-income households have sufficient funds to make ends meet.

While federal leadership is imperative, provincial and territorial governments’ engagement in policies to reduce food insecurity is also critical. Given that the provinces and territories are responsible for health care, they bear the costs of food insecurity insofar as it increases people’s needs for health services. There are clear differences in food insecurity prevalence across the provinces and territories and within some jurisdictions (notably Quebec) over time. The effects of specific provincial/territorial policies on food insecurity rates warrant much more evaluation. What is known suggests that provincial and territorial government actions matter. Many important policy levers rest with the provinces and territories. They are responsible for social assistance, they set minimum wages and employment standards, they deliver social housing programs, they levy taxes and deliver tax credits, and many provide child benefits.

It’s time to recognize food insecurity is a serious public health problem in Canada, a problem that is only getting worse. Without deliberate, evidence-based policy interventions by federal, provincial and territorial governments, this problem will continue to fester.

For more information, see the Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017-18 report