Food Insecurity and Social Assistance

June 27, 2016

This factsheet is based on data from previous Statistics Canada Surveys and has not been updated or maintained. It is provided here for archival purposes. Updated data can be found in the latest status report on household food insecurity in Canada.

Food insecurity – the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints – is a serious public health problem in Canada. It negatively impacts physical, mental, and social health, and costs our healthcare system considerably.

Statistics Canada began monitoring food insecurity in 2005 through the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Since then, food insecurity has persisted across Canada, with over 4 million Canadians living in food insecure households.

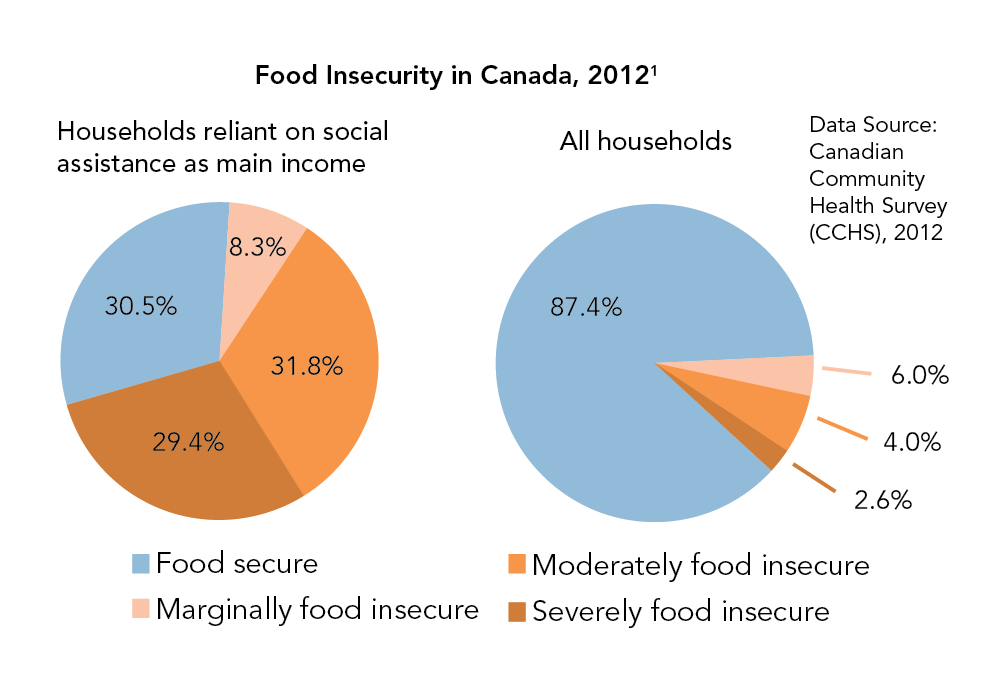

Social assistance programs* vary among provinces and territories, and food insecurity rates among recipients fluctuate from year to year within jurisdictions. However, being on social assistance anywhere in Canada poses an extremely high risk to food insecurity.1

Nearly one third of households reliant on social assistance as their main source of income are severely food insecure, indicating serious levels of food deprivation. The rate of severe food insecurity among social assistance recipients is 11 times higher than the rate nationally.1

The high rates of food insecurity among households reliant on social assistance suggest that these support programs are failing to enable recipients to meet their basic needs.

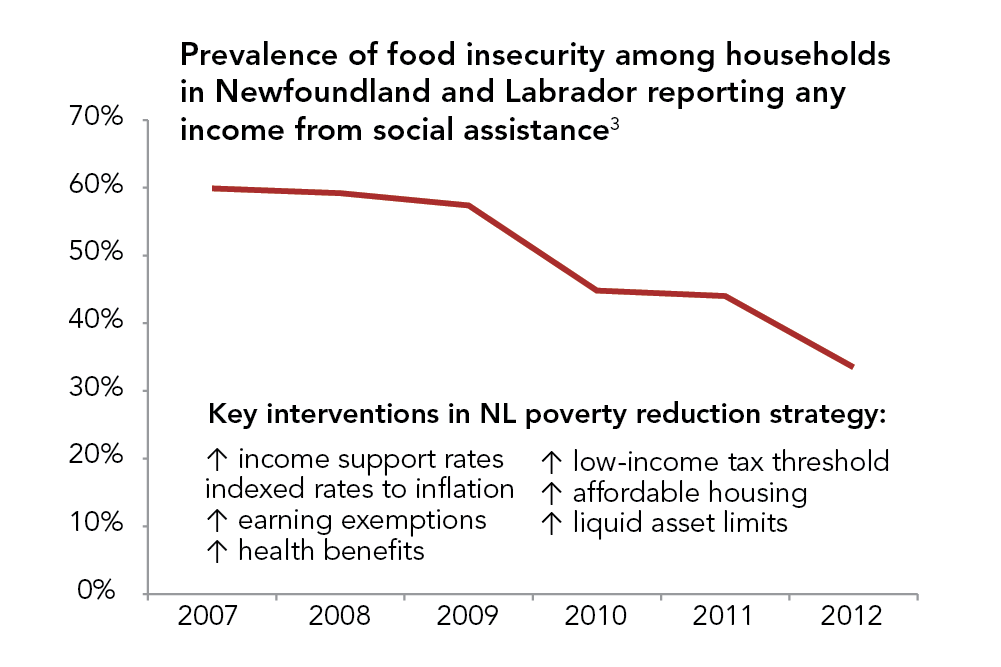

The notably lower rate of food insecurity among social assistance recipients in Newfoundland and Labrador is linked to the impact of policy reforms introduced as part of their poverty reduction strategy in 2006.3

Further evidence of the sensitivity of food insecurity among social assistance recipients to policy changes is the temporary drop in rates in British Columbia, following a one-time increase in income support in 2006.4

Given the extreme vulnerability of social assistance recipients and the evidence that policy interventions can reduce their food insecurity, provincial and territorial governments need to reform current programs to ensure that recipients can meet their basic needs, tracking food insecurity rates to assess the success of program changes.

*The data available from CCHS do not allow us to differentiate people on disability support programs from those receiving general welfare assistance.

References

- Tarasuk, V, Mitchell, A, Dachner, N. (2014). Household food insecurity in Canada, 2012. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from http://proof.utoronto.ca

- Tarasuk, V, Mitchell, A, Dachner, N. (2016). Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from http://proof.utoronto.ca

- Loopstra, R., Dachner, N., & Tarasuk, V. (2015). An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007-2012. Canadian Public Policy, 41(3), 191-206. https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/cpp.2014-080

- Li, N., Dachner, N., & Tarasuk, V. (2016). The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Preventive Medicine, 93, 151-158. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743516303048