Children in Food Insecure Households

June 27, 2016

This factsheet is based on data from previous Statistics Canada Surveys and has not been updated or maintained. It is provided here for archival purposes. Updated data can be found in the latest status report on household food insecurity in Canada.

Food insecurity – the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints – is a serious public health problem in Canada. It negatively impacts physical, mental, and social health, and costs our healthcare system considerably.

Statistics Canada began monitoring food insecurity in 2005 through the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Since then, food insecurity has persisted across Canada, with over 4 million Canadians living in food insecure households.

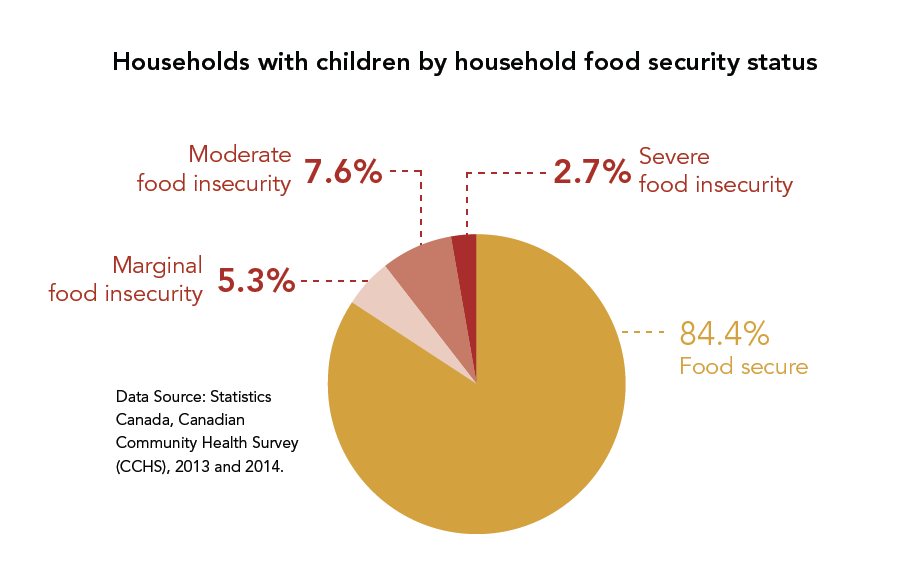

Food insecurity is more prevalent among households with children under the age of 18, particularly those headed by single mothers.1

Exposure to severe food insecurity leaves an indelible mark on children’s wellbeing, manifesting in greater risks for conditions like asthma, depression, and suicidal ideation in adolescence and early adulthood.2, 3

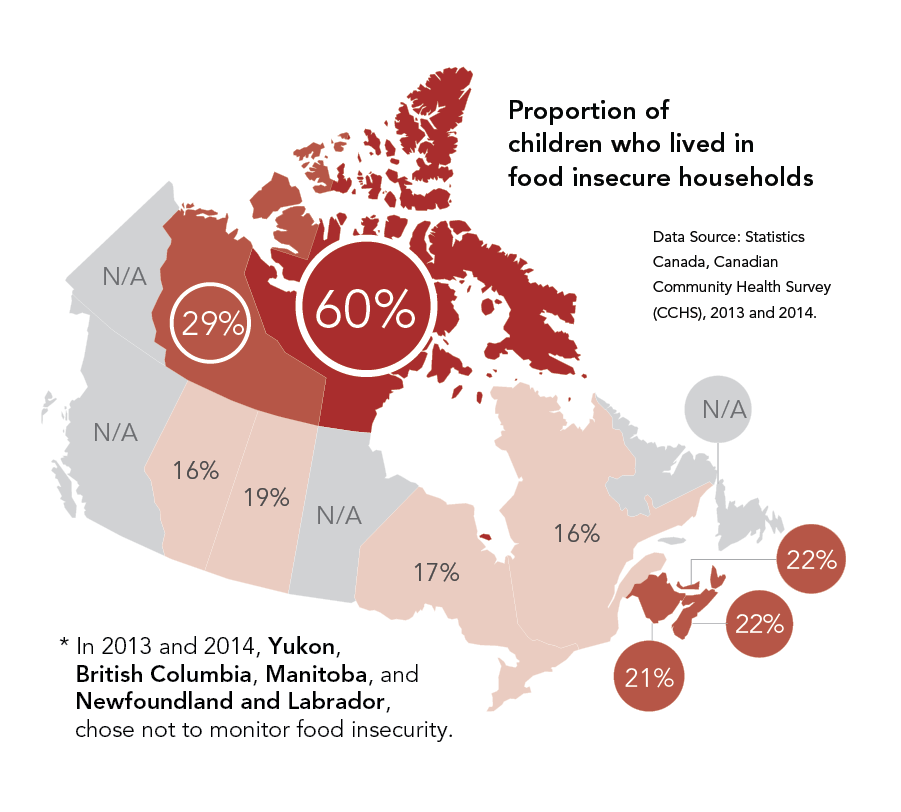

Among the provinces and territories that monitored food insecurity in 2013-2014*:

- 17.2% of children lived in households affected by food insecurity.

- Two-thirds of these children were in moderately or severely food insecure households.

- Over half the children living in Nunavut lived in food insecure households, the highest rate in Canada.

- The Northwest Territories had the second highest prevalence of children living in food insecure households at 29%.

- The Maritime provinces, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick had rates above 20%, meaning more than 1 in 5 children were affected in these provinces.

- The lowest prevalence of children in food-insecure families was found in Quebec and Alberta, both at 16%, but even in these cases, almost 1 in 6 children were affected.

* In 2013 and 2014, Yukon, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador, chose not to monitor food insecurity.

References

- Tarasuk, V, Mitchell, A, Dachner, N. (2016). Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from http://proof.utoronto.ca

- Kirkpatrick, S. I., McIntyre, L., & Potestio, M. L. (2010). Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(8), 754-762. http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=383613

- McIntyre, L., Williams, J. V., Lavorato, D. H., & Patten, S. (2013). Depression and suicide ideation in late adolescence and early adulthood are an outcome of child hunger. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(1), 123-129. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032712007823