Updated 2023-11-23 for updated statistics from our report, Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2022

As Canada commemorates the seventh anniversary of the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), it is essential to reflect on the program’s design and its role in addressing household food insecurity among families with children. Launched in 2016, the CCB was heralded as a crucial step towards alleviating child poverty and continues to be touted as a major policy success. However, examining the program through the lens of food insecurity paints a different picture.

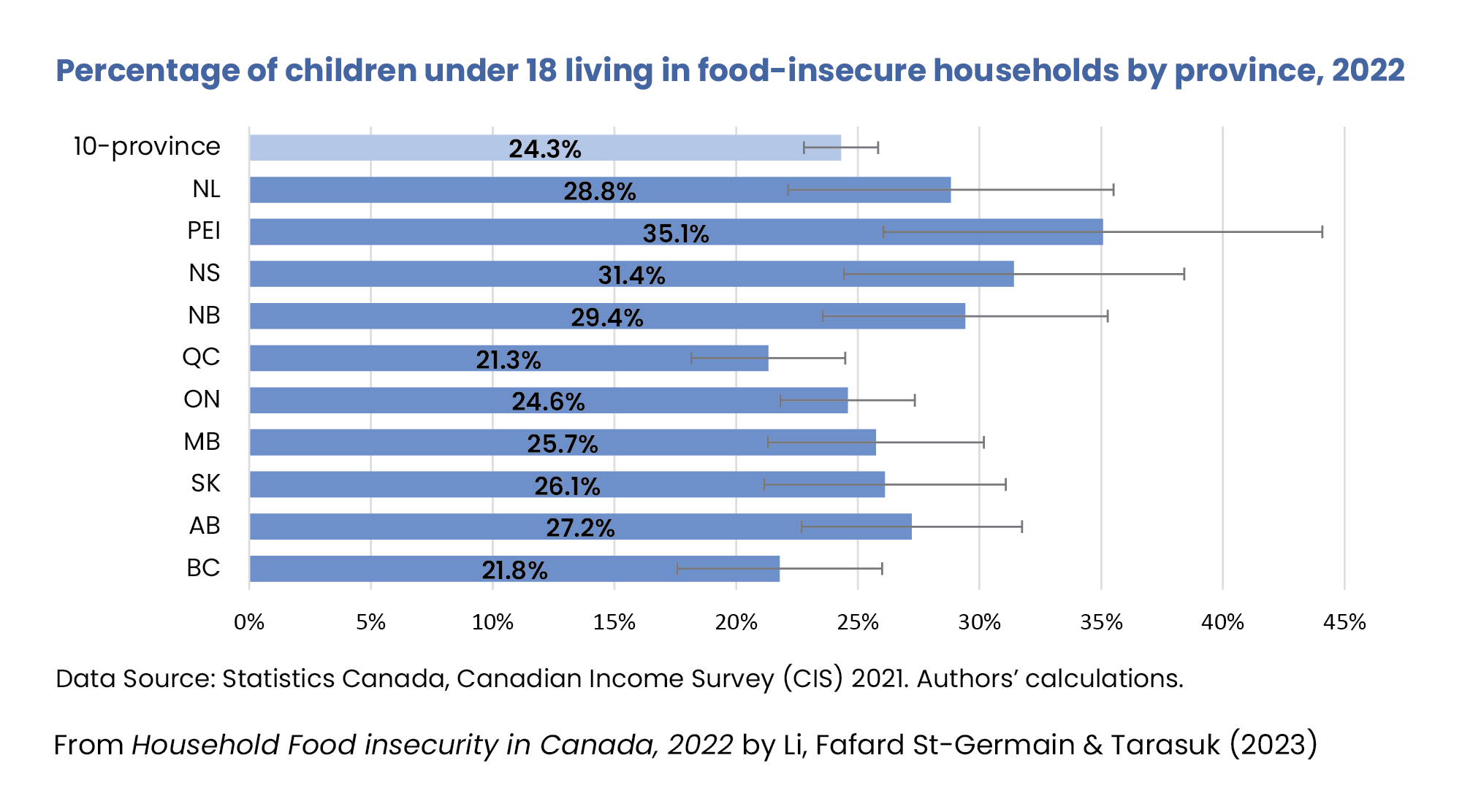

The latest statistics show that 1 in 4 children in the ten provinces (24.3%), or almost 1.8 million children, lived in a food-insecure family in 2022. This is the highest number and percentage documented to date.

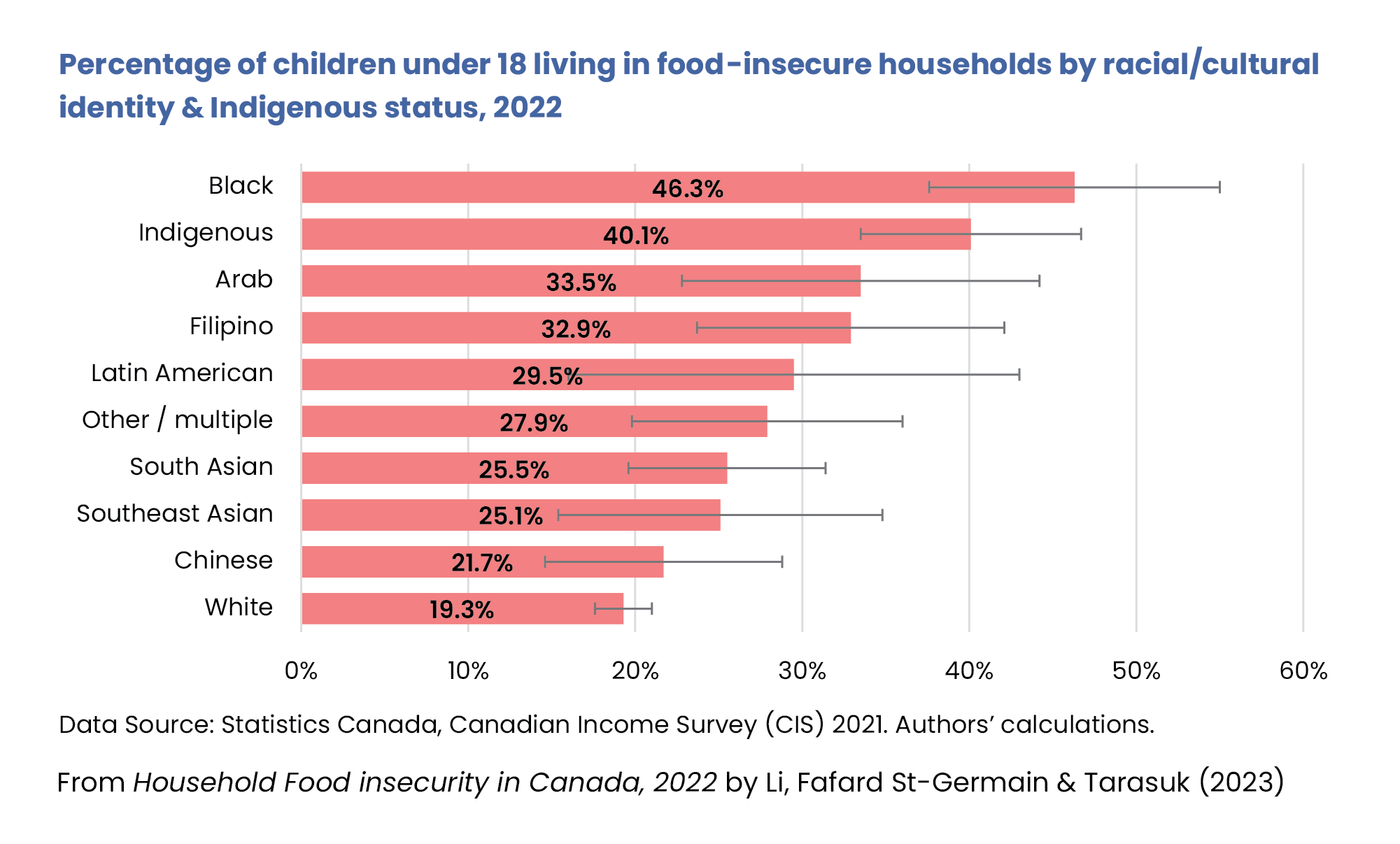

The racial disparities in food insecurity also appear in the percentage of children living in food-insecure households. In 2022, 46.3% of Black children and 40.1% of Indigenous children livied in a food-insecure household.[1]

Most of the increase in food insecurity from 2021 to 2022 was among households with children. Of the 312,000 more food-insecure households in 2022, over half (62.8%) were households with at least one child under the age of 18, despite these households only making up 34.2% of all the households living in the 10 provinces.

Providing more financial support to low-income households reduces their risk of food insecurity; the persistently high rate of food insecurity among families with children suggests that the CCB isn’t providing enough support for families that really need it.

Although the CCB was not designed to reduce food insecurity among Canadian families, our research on the impact of the benefit shows it has unrealized potential to do so and points to some key recommendations if it were to be redesigned to explicitly target the rate of food insecurity.

The Recommendations

- Increase the benefit amount for low-income families.

- Equalizing benefit amounts for families with children over 6 years old so that they aren’t receiving less when their children turn 6.

- Create a federal CCB supplement for remote and Northern communities to address the exceedingly high percentage of food-insecure households and elevated costs of living.

The Evidence

The federal government introduced the CCB in 2016, which consolidated and replaced existing child benefit programs and provided more money to families. PROOF’s examination of food insecurity before and after the implementation of the CCB revealed there was no change in the overall prevalence of food insecurity for families with children after.

However, we were able to identify a reduction in severe food insecurity, which captures the most extreme experiences of food deprivation due to financial constraint (e.g., missing meals to going whole days without eating). This reduction in severe food insecurity was particularly pronounced for low-income households.

These findings highlight how modest increases to household incomes, like those implemented in the change to the CCB, can impact the risk of food insecurity. It also illustrates the the need to design policy interventions with this outcome in mind to order to maximize their potential.

In a more recent study, we leveraged the fact that the CCB is larger for families with children under 6 years of age, up to $1,068 more annually, to examine the impact of a more generous benefit. By matching CCB-receiving families with and without children under 6 across a suite of sociodemographic characteristics known to predict risk of food insecurity, we found the families that received the extra money provided to families with younger children had a lower risk of food insecurity.

The effect of this relatively small amount of extra money from the CCB (on average $724 more per year or $60 more per month) appeared to be even stronger for families with low incomes, renters, and lone-parent families.

Raising the size of the CCB for low-income families (i.e., the group most vulnerable to food insecurity) would reduce their risk of food insecurity. The findings also support the idea of equalizing the benefit for families with children over 6 in recognition of the high rates of food insecurity among those families. At it stands, the current design of the CCB ignores the needs of those with older children.

These studies are part of a larger body of evidence demonstrating the need for income-based interventions to move the needle on food insecurity, including international research on the impact of child benefits.

The need to focus on targeting and reducing household food insecurity

Over the past seven years, the CCB has been credited for reducing the rate of child poverty. However, this statistic provides limited information on whether families are actually better off.

The measure of food insecurity captures financial hardship in a way that income-based measures of poverty, like Canada’s Official Poverty Line, do not. By identifying whether households have difficulty affording food, we learn more about their broader financial circumstances.

The deprivation captured by household food insecurity is the product of household income, the stability and security of that income over the year, assets like homeownership, access to financial resources outside of income like savings, credit, or help from family or friends, debt, and cost of living.

Food insecurity is also a potent, independent social determinant of health. The relationship between food insecurity and poor health persists even after taking into consideration differences in income and other sociodemographic characteristics.

Besides having poorer diets, children living in food-insecure households are more likely to also experience hyperactivity and inattention, have poor academic achievement, and develop serious mental health problems when exposed to severe food insecurity.

The health disadvantages are evidence almost from birth, with infants born to food-insecure mothers more likely to be treated in emergency departments and mothers unable to follow recommendations for optimal infant nutrition.

New research has found that children and adolescents living in food-insecure households in Ontario required more health care services for mental or substance use disorders than those living in food secure households and incurred greater healthcare costs.

Together, research on the relationship between health and food insecurity points to the broader impact of pervasive material deprivation and household financial hardship, not just dietary compromise — and therefore to solutions that address income inadequacy and instability.

As an entirely preventable social determinant of child health, reducing food insecurity among families with children should be a priority.

The CCB as a policy lever to reduce food insecurity

Although the CCB was not designed to reduce food insecurity, it is well-positioned as one of the major federal policy levers to do so, with several positive existing design features.

It is a tax-free benefit that is paid monthly, meaning it provides a reliable source of income support throughout the year without affecting the receipt of other benefits like social assistance. It is income-tested and automatically determined through tax filing, so there are fewer barriers and eligibility criteria. Critically, it has been indexed to inflation since 2018, helping benefit amounts keep up with the rising cost of living.

Reallocating funds currently directed towards very high-income families (i.e., those with negligible risk of food insecurity) could support a more impactful policy design without incurring additional costs. Implementing quarterly indexing, similar to the federal government’s approach for OAS and GIS, could make the CCB more responsive to inflation. Presently, the CCB is indexed annually based on the previous year’s average inflation rate.

Realizing the unrealized potential of the Canada Child Benefit

Having marked the seventh anniversary of the CCB, it is time to acknowledge the need for redesigning the benefit to have a greater impact on food insecurity. The current design falls short of providing enough support to those who need it most.

A redesigned CCB with increased benefit amounts for low-income families, equalized benefits for families with older children, and more consideration for families in the North facing higher costs of living would be a key part of federal action to reduce food insecurity.

Related posts:

The Canada Child Benefit as a Policy to Improve Children’s Health (HESA submission)

A more generous Canada Child Benefit for low-income families would reduce their probability of food insecurity

Commentary | Story

Canada Child Benefit’s Seventh Year: Reflecting on its unrealized potential to reduce food insecurity

July 21, 2023

Updated 2023-11-23 for updated statistics from our report, Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2022

As Canada commemorates the seventh anniversary of the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), it is essential to reflect on the program’s design and its role in addressing household food insecurity among families with children. Launched in 2016, the CCB was heralded as a crucial step towards alleviating child poverty and continues to be touted as a major policy success. However, examining the program through the lens of food insecurity paints a different picture.

The latest statistics show that 1 in 4 children in the ten provinces (24.3%), or almost 1.8 million children, lived in a food-insecure family in 2022. This is the highest number and percentage documented to date.

The racial disparities in food insecurity also appear in the percentage of children living in food-insecure households. In 2022, 46.3% of Black children and 40.1% of Indigenous children livied in a food-insecure household.[1]

Most of the increase in food insecurity from 2021 to 2022 was among households with children. Of the 312,000 more food-insecure households in 2022, over half (62.8%) were households with at least one child under the age of 18, despite these households only making up 34.2% of all the households living in the 10 provinces.

Providing more financial support to low-income households reduces their risk of food insecurity; the persistently high rate of food insecurity among families with children suggests that the CCB isn’t providing enough support for families that really need it.

Although the CCB was not designed to reduce food insecurity among Canadian families, our research on the impact of the benefit shows it has unrealized potential to do so and points to some key recommendations if it were to be redesigned to explicitly target the rate of food insecurity.

The Recommendations

The Evidence

The federal government introduced the CCB in 2016, which consolidated and replaced existing child benefit programs and provided more money to families. PROOF’s examination of food insecurity before and after the implementation of the CCB revealed there was no change in the overall prevalence of food insecurity for families with children after.

However, we were able to identify a reduction in severe food insecurity, which captures the most extreme experiences of food deprivation due to financial constraint (e.g., missing meals to going whole days without eating). This reduction in severe food insecurity was particularly pronounced for low-income households.

These findings highlight how modest increases to household incomes, like those implemented in the change to the CCB, can impact the risk of food insecurity. It also illustrates the the need to design policy interventions with this outcome in mind to order to maximize their potential.

In a more recent study, we leveraged the fact that the CCB is larger for families with children under 6 years of age, up to $1,068 more annually, to examine the impact of a more generous benefit. By matching CCB-receiving families with and without children under 6 across a suite of sociodemographic characteristics known to predict risk of food insecurity, we found the families that received the extra money provided to families with younger children had a lower risk of food insecurity.

The effect of this relatively small amount of extra money from the CCB (on average $724 more per year or $60 more per month) appeared to be even stronger for families with low incomes, renters, and lone-parent families.

Raising the size of the CCB for low-income families (i.e., the group most vulnerable to food insecurity) would reduce their risk of food insecurity. The findings also support the idea of equalizing the benefit for families with children over 6 in recognition of the high rates of food insecurity among those families. At it stands, the current design of the CCB ignores the needs of those with older children.

These studies are part of a larger body of evidence demonstrating the need for income-based interventions to move the needle on food insecurity, including international research on the impact of child benefits.

The need to focus on targeting and reducing household food insecurity

Over the past seven years, the CCB has been credited for reducing the rate of child poverty. However, this statistic provides limited information on whether families are actually better off.

The measure of food insecurity captures financial hardship in a way that income-based measures of poverty, like Canada’s Official Poverty Line, do not. By identifying whether households have difficulty affording food, we learn more about their broader financial circumstances.

The deprivation captured by household food insecurity is the product of household income, the stability and security of that income over the year, assets like homeownership, access to financial resources outside of income like savings, credit, or help from family or friends, debt, and cost of living.

Food insecurity is also a potent, independent social determinant of health. The relationship between food insecurity and poor health persists even after taking into consideration differences in income and other sociodemographic characteristics.

Besides having poorer diets, children living in food-insecure households are more likely to also experience hyperactivity and inattention, have poor academic achievement, and develop serious mental health problems when exposed to severe food insecurity.

The health disadvantages are evidence almost from birth, with infants born to food-insecure mothers more likely to be treated in emergency departments and mothers unable to follow recommendations for optimal infant nutrition.

New research has found that children and adolescents living in food-insecure households in Ontario required more health care services for mental or substance use disorders than those living in food secure households and incurred greater healthcare costs.

Together, research on the relationship between health and food insecurity points to the broader impact of pervasive material deprivation and household financial hardship, not just dietary compromise — and therefore to solutions that address income inadequacy and instability.

As an entirely preventable social determinant of child health, reducing food insecurity among families with children should be a priority.

The CCB as a policy lever to reduce food insecurity

Although the CCB was not designed to reduce food insecurity, it is well-positioned as one of the major federal policy levers to do so, with several positive existing design features.

It is a tax-free benefit that is paid monthly, meaning it provides a reliable source of income support throughout the year without affecting the receipt of other benefits like social assistance. It is income-tested and automatically determined through tax filing, so there are fewer barriers and eligibility criteria. Critically, it has been indexed to inflation since 2018, helping benefit amounts keep up with the rising cost of living.

Reallocating funds currently directed towards very high-income families (i.e., those with negligible risk of food insecurity) could support a more impactful policy design without incurring additional costs. Implementing quarterly indexing, similar to the federal government’s approach for OAS and GIS, could make the CCB more responsive to inflation. Presently, the CCB is indexed annually based on the previous year’s average inflation rate.

Realizing the unrealized potential of the Canada Child Benefit

Having marked the seventh anniversary of the CCB, it is time to acknowledge the need for redesigning the benefit to have a greater impact on food insecurity. The current design falls short of providing enough support to those who need it most.

A redesigned CCB with increased benefit amounts for low-income families, equalized benefits for families with older children, and more consideration for families in the North facing higher costs of living would be a key part of federal action to reduce food insecurity.

Related posts:

The Canada Child Benefit as a Policy to Improve Children’s Health (HESA submission)

A more generous Canada Child Benefit for low-income families would reduce their probability of food insecurity