The Big Story Podcast: Why food banks can’t solve the problem of hungry Canadians

January 26, 2023

Dr. Valerie Tarasuk joined The Big Story Podcast to talk about the need for policy action on income inadequacy, in order to address the high and persistent rate of household food insecurity in Canada.

Listen below and on your favourite podcast platforms at The Big Story Podcast:

Key takeaways

Food insecurity = pervasive material deprivation

The deprivation experienced by households that are food-insecure is not confined to food. Food-insecure households are likely making compromise to all sort of necessities, including housing and prescription medication.

“We identify somebody as food insecure through asking all these questions about their access to food, but what we’re really doing is identifying individuals and families with pervasive material deprivation that is rooted in an inability to meet basic needs with their existing sources of revenue.”

Addressing food insecurity means making sure households have enough money for their basic needs.

The way to address food insecurity is to address the underlying problem of inadequate and insecure income. When we look at who is food insecure in Canada, we can see that food insecurity reflects major social and economic inequities and how our public policies have left low-income Canadians, particularly working age adults and their families, behind for a long time.

“We’ve got a whole lot of people, both people in the workforce and people relying on social assistance or welfare disability payments, who are unable to make ends meet routinely because the cash flow is simply not sufficient or not reliably sufficient to cover basic costs of things like food and rent.”

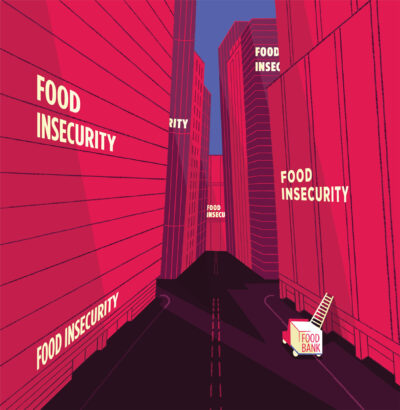

Food charity is unable to solve this problem.

Food charities do their best to support their communities in times of need, but the temporary food relief is ultimately unable to address the circumstances underlying their experiences of deprivation.

With a history of over 40 years, food charity has become the dominant response to food insecurity. However, it is clear that this problem has only festered. We won’t be able to move the needle on food insecurity until we start addressing the core problem, instead of its symptoms.

Provincial and territorial policies matter for food insecurity.

Differences in the prevalence of food insecurity across the provinces and territories point to the important roles their governments have in protecting households from food insecurity. Research has shown that minimum wage, social assistance rates, income taxes, and child benefits are policy levers for these governments to have an impact on this problem.

Quebec has pulled apart from the other provinces by having a considerably lower rate of food insecurity in recent years. Living in Quebec has also repeatedly been shown to be protective against food insecurity. While more research is needed to determine the reasons, it may reflect the province’s more progressive policies and stronger social safety net, such as more generous social assistance programs, child benefits, and childcare policies.

Time to get serious about basic income.

A basic income guarantee is promising way to tackle food insecurity because it could provide low-income households, regardless of their income source, with a livable income that is both adequate and secure. Half of food insecure households rely on employment incomes and there is currently few policies to mitigate the financial difficulties they face the way public old-age pensions have for seniors. Research on these programs (Old Age Security and Guarantee Income Supplement) have shown a substantial drop in the risk of food insecurity for unattached, low-income adults, once they become eligible at age 65.

“The findings around the very positive impact of our public pension system for seniors have taken us into thinking about basic income because that’s the closest idea we’ve got. When you hit 65, what we’ve got is an income floor below which we do not let people fall and that income floor is relatively adequate — not perfect, depending on where you are and what else you have to cope with — but still substantially better than anything we’re doing for people under 65.”

Recognizing the root cause of food insecurity and the kinds of effective responses as a start to policy action

There is wide consensus that policies to ensure adequate incomes are what is needed to address food insecurity. Yet charitable food provision remains the main way this problem is discussed in Canada. The government funding of food charity in response to food insecurity further entrenches an ineffective approach to the problem and downloads the responsibility for a social safety net onto ad hoc community organizations. Shifting the onus and conversation back to public policy is critical for making progress on food insecurity reduction.

“I do feel like there’s a way in which our political leaders have been gliding along without really any accountability for the fact that this problem continues to fester and probably right now is getting worse, and meanwhile they’re telling us all to donate, and periodically they’re throwing small amounts of money at the [food charity] system as well. I think that’s a part of the problem in Canada that we’re going to have to reckon with.”