Food insecurity: A problem of inadequate income, not solved by food

October 13, 2022

Charitable food programs have been the primary response to household food insecurity in Canada since the 1980s. Yet, for as long as there has been systematic monitoring, there has been no meaningful decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity.

Based on the most recent data from Statistic Canada’s Canadian Income Survey, almost 1 in 6 people in the ten provinces lived in a food-insecure household in 2021.[1]* This amounts to 5.8 million Canadians, which is an underestimate considering that data on the territories are not yet available and the survey does not include people living on First Nations reserves, in some remote Northern areas, or who are homeless.[1]

Research into what it means to be food insecure helps explain why interventions centred around food have such limited impact — they fail to address the underlying problem of inadequate income. Food-insecure households do not only make compromises to food but also to other basic needs. The health consequences of food insecurity extend far beyond poor nutrition.

If the spotlight remains on the lack of food, it keeps the extensive compromises and health consequences these households face in the dark. It also leads us away from policy interventions that ensure wages and income supports are sufficient for them to meet their basic needs.

Compromises to food are only part of the pervasive deprivation food-insecure households face.

Food insecurity is an important marker of dietary compromise with food-insecure households spending less on food and having poorer quality diets, which decline with increasing severity of food insecurity.[2]

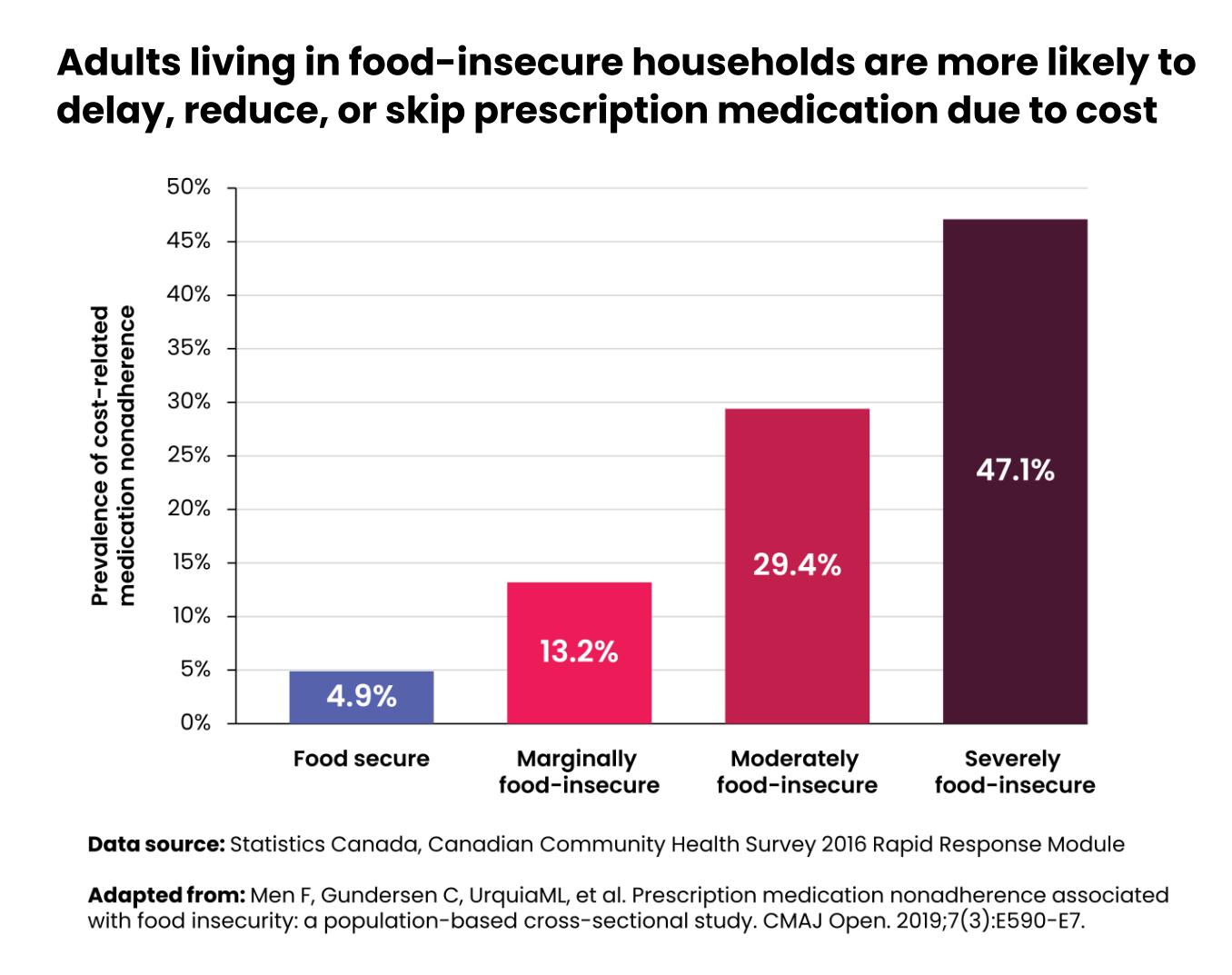

However, these compromises are part of a wider spectrum of trade-offs. Compared with food-secure households, food-insecure households spend substantially less on their essential needs such as housing, clothing, transportation, and personal care.[2][3] In addition, food-insecure adults may delay, reduce, or skip prescription medications because they can’t afford them. This cost-related medication nonadherence is associated with worsening health and greater use of health care services.[4]

The breadth of health problems associated with food insecurity goes beyond diet-related conditions.

While food insecurity is associated with poor nutrition and diet-related diseases like diabetes,[3][5] its effects on health extend beyond conditions related to food and nutrition.

Food-insecure adults are more likely to also have a wide range of physical and mental health problems including mood and anxiety disorders,[6] depression,[7][8] infectious diseases,[9][10] chronic pain,[11] and poor oral health.[12] New research shows that food-insecure adults and adolescents face greater risk of injury.[13]

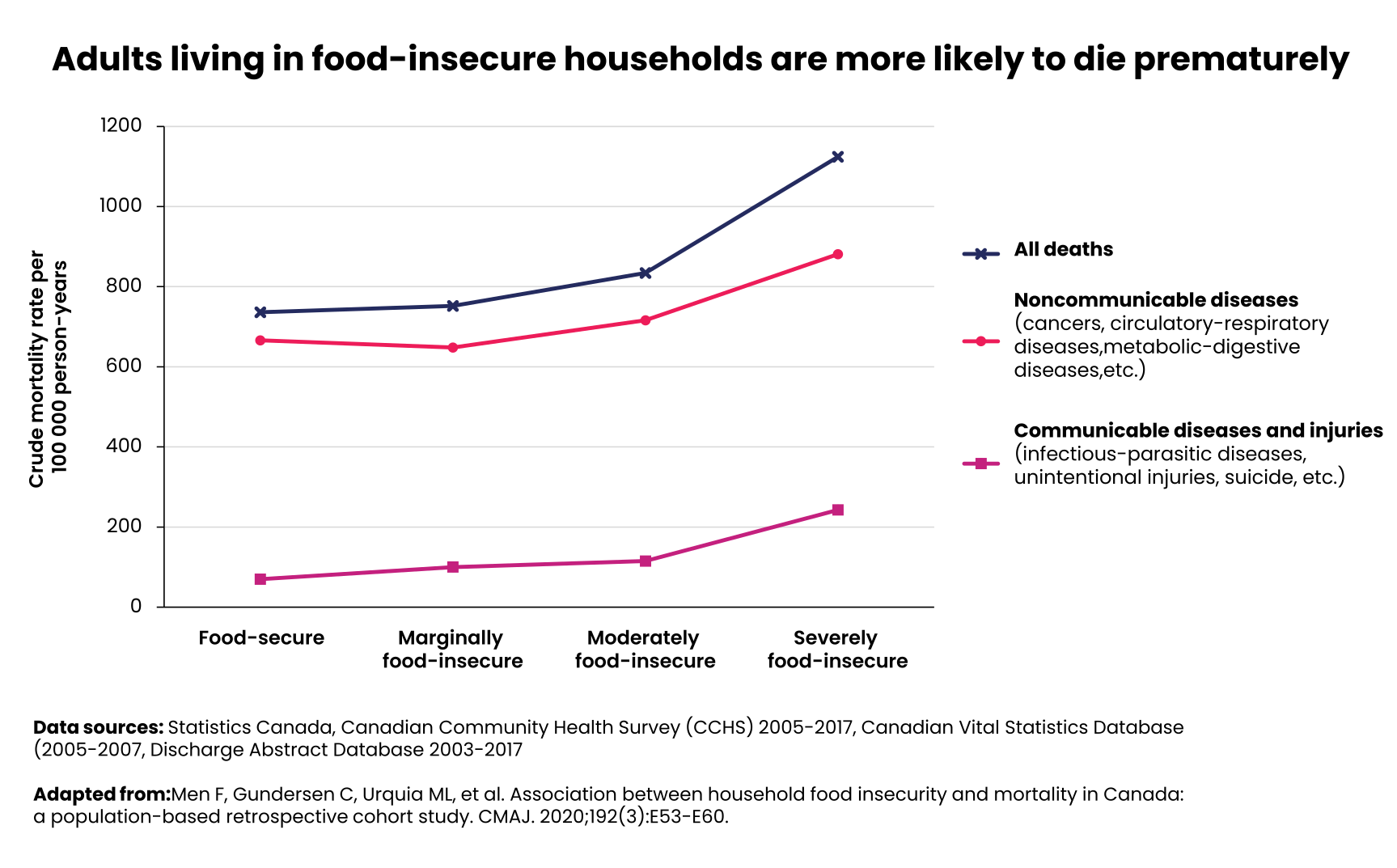

This story continues to play out in the relationship between food insecurity and premature death (i.e., before the age of 83). While infectious-parasitic diseases, injuries, and suicides make up only a small proportion of premature deaths in Canada, the increase in risk of dying from these causes is especially great for severely food-insecure adults.[14] They are more than twice as likely to die from these causes than their food-secure counterparts.

The vast majority of premature deaths for both food-secure and food-insecure adults in Canada are caused by non-communicable diseases, but it is clear that these too take a much greater toll on the food-insecure.[14]

Interventions that focus on food and not households’ financial circumstances miss the bigger picture.

Understanding food insecurity as a marker of a pervasive material deprivation and profound health inequity helps direct us to approaches to this problem that are effective.

The long history of food charity in Canada has produced a massive network of non-profit food providers,[15] but there has been no progress on food insecurity reduction because food assistance programs provide, at most, temporary food relief.[16][17][18][19]

There is also no evidence that other food-based interventions, such as food literacy education, alternative food retail, or community gardens, can reduce food insecurity.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Ultimately, these approaches are unable to resolve the broader experiences of deprivation and the underlying inadequate financial circumstances.

On the other hand, income-based interventions treat the core problem rather than its symptoms. Research has repeatedly shown that policies that improve the financial situation of low-income households reduce their risk of food insecurity.[27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

Policies like minimum wage, social assistance, progressive taxation, child benefits, public pensions, and other income transfers must do more to support sufficient and stable incomes. It is also clear that systemic manifestations of racism and colonialism drive the high rates of food insecurity among Black and Indigenous households.[34][35] More attention must be paid to the socioeconomic and policy conditions that give rise to food insecurity.

Shifting the focus from food to income policies

Government response to food insecurity has continued to focus on food, with increased funding recently going towards charitable food initiatives.[36][37][38][39][40] This government response must end. The persistently high rates of food insecurity are a telling sign that there needs to be a concerted effort to restructure federal, provincial, and territorial policies to ensure Canadians have enough money for their basic needs.

Given the abundance of evidence on what it means to be food-insecure and the ability for income-based interventions to reduce food insecurity, the way forward lies in treating this problem as what it actually is — a problem of income inadequacy, not solved by food.

* Statistics for the territories in 2021 from the 2020 Canadian Income Survey (CIS) are not available at the time of this publication. Estimates from the 2018 and 2019 CIS show very high rates of food insecurity in the territories.

References

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF); 2022.

- Fafard St-Germain AA, Tarasuk V. Prioritization of the essentials in the spending patterns of Canadian households experiencing food insecurity. Public Health Nutrition. 2018;21(11):2065-78.

- Hutchinson J, Tarasuk V. The relationship between diet quality and the severity of household food insecurity in Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2021:1-14.

- Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, et al. Prescription medication nonadherence associated with food insecurity: a population-based cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(3):E590-E7.

- Tait C, L’Abbe M, Smith P, et al. The association between food insecurity and incident type 2 diabetes in Canada: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0195962.

- Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM -Population Health. 2017;3:464-72.

- Tarasuk V, Gundersen C, Wang X, et al. Maternal food insecurity is positively associated with postpartum mental disorders in Ontario, Canada. J Nutr. 2020;150(11):3033-40.

- Shafiee M, Vatanparast H, Janzen B, et al. Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms in the Canadian adult population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;279:563-71.

- Cox J, Hamelin AM, McLinden T, et al. Food insecurity in HIV-hepatitis C virus co-infected individuals in Canada: the importance of co-morbidities. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;21(3):792-802.

- Bekele T, Globerman J, Watson J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among people living with HIV affiliated with AIDS service organizations in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care. 2018;30(5):663-71.

- Men F, Fischer B, Urquia ML, et al. Food insecurity, chronic pain, and prescription opioid use. SSM-Public Health. 2021;14.

- Muirhead V, Quinonez C, Figueriredo R, et al. Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2009;37:294-304.

- Men F, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. Examining the relationship between food insecurity and causes of injury in Canadian adults and adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1557.

- Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, et al. Association between household food insecurity and mortality in Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2020;192(3):E53-E60.

- Nikkel L, Summerhill V, Gooch M, et al. Canada’s Invisible Food Network. Ontario, Canada: Second Harvest and Value Chain Management International; 2021.

- Enns A, Rizvi A, Quinn S, et al. Experiences of food bank access and food insecurity in Ottawa, Canada. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. 2020;15(4):456-72.

- Holmes E, Black J, Heckelman A, et al. “Nothing is going to change three months from now”: a mixed methods characterization of food bank use in Greater Vancouver. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;200:129-36.

- Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. The relationship between food banks and household food insecurity among low-income Toronto families. Canadian Public Policy. 2012;38(4):497-514.

- Tarasuk V, Fafard St-Germain AA, Loopstra R. The relationship between food banks and food insecurity: insights from Canada. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2019;31(5):841-52.

- Huisken A, Orr S, Tarasuk V. Adults’ food skills and use of gardens are not associated with household food insecurity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;107(6):e526–e32.

- Kirkpatrick S, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity and participation in community food programs among low-income Toronto families. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2009;100(2):135-9.

- Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. Perspectives on community gardens, community kitchens and the Good Food Box program in a community-based sample of low-income families. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2013;104(1):e55-e9.

- Blanchet R, Loewen OK, Godrich SL, et al. Exploring the association between food insecurity and food skills among school-aged children. Public Health Nutrition. 2020;23(11):2000-5.

- Pepetone A, Vanderlee L, White CM, et al. Food insecurity, food skills, health literacy and food preparation activities among young Canadian adults: a cross-sectional analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(9):2377-87.

- Little M, Rosa E, Heasley C, et al. Promoting Healthy Food Access and Nutrition in Primary Care: A Systematic Scoping Review of Food Prescription Programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2021;36(3):518-536.

- Miewald C, Holben D, Hall P. Role of a Food Box Program: In Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Food Security. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2012;73(2):59-65.

- Brown E, Tarasuk V. Money speaks: Reductions in severe food insecurity follow the Canada Child Benefit. Prev Med. 2019;129:105876.

- Ionescu-Ittu R, Glymour M, Kaufman J. A difference-in-difference approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Preventive Medicine. 2015;70:108-16.

- Men F, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. The role of provincial social policies and economic environment in shaping household food insecurity among families with children in Canada. Preventive Medicine. 2021;148:106558.

- Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005-2012. Preventive Medicine. 2016;93:151-8.

- Tarasuk V, Li N, Dachner N, et al. Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 2005-2014. Canadian Public Policy. 2019;45(1):93-104.

- Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007-2012. Canadian Public Policy. 2015;41(3):191-206.

- McIntyre L, Dutton D, Kwok C, et al. Reduction of food insecurity in low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a Guaranteed Annual Income. Canadian Public Policy. 2016;42(3):274-86.

- Dhunna S, Tarasuk V. Black-white racial disparities in household food insecurity from 2005-2014, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2021:1-15.

- Tarasuk V, Fafard St-Germain A-A, Mitchell A. Geographic and socio-demographic predictors of household food insecurity in Canada, 2011–12. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):12.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Local Food Infrastructure Fund: Applicant guide. 2019.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Emergency Food Security Fund. 2021. [updated 2021-12-22].

- Office of the Premier. Ontario Protecting the Most Vulnerable During COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. [updated March 23, 2020].

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Province supporting B.C.’s food banks during COVID-19. 2020. [updated March 29, 2020].

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Provincial Government Partnering with Community to Support Food Sharing Programs. 2020. [updated March 25, 2020].