Map of PEI modified from NordNordWest under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Earlier this month, MLAs in PEI unanimously passed the first bill in Canada that sets explicit and binding targets for food insecurity reduction. The Poverty Elimination Strategy Act, tabled by Green MLA Hannah Bell, establishes targets for reducing the rates of poverty, food insecurity, and chronic homelessness on the Island.[1]

By passing this bill, the government commits to eliminating food insecurity among children and halving the provincial rate of food insecurity by 2025. The goal is to eliminate food insecurity in PEI entirely by 2030.[1]

Targets established by the Poverty Elimination Strategy Act[1]

By 2025:

- Reduce the PEI poverty rate for 2018 by 25% among all persons.

- Reduce the PEI poverty rate for 2018 by 50% among children under 18 years of age.

- Reduce food insecurity among all persons by 50%,

- Reduce food insecurity among children to 0%,

- Reduce chronic homelessness among all persons to 0%

By 2030:

- Reduce the PEI poverty rate for 2023 by 50% among all persons.

- Reduce the PEI poverty rate for 2023 by 100% among children under 18 years of age.

- Reduce food insecurity among all persons to 0%

By 2035:

- Reduce the PEI poverty rate for 2029 by 100% among all persons.

While federal, provincial, and territorial governments have all committed to poverty reduction strategies, only some have any specific, measurable targets (Federal, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and now PEI). Other than PEI, none have declared food insecurity reduction targets or commitments to fully eliminate poverty.

The next steps for PEI should be to re-evaluate their poverty reduction plans and ensure that the actions taken are evidence-based and move them towards these targets.

Statistics Canada measures food insecurity using the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) on the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The HFSSM consists of 18 questions about the experiences of food insecurity, ranging from worrying about running out of food to going whole days without eating, due to financial constraint.

Food insecurity in PEI

Based on the most recently available data, 14.0% of households in PEI were food-insecure in 2017-2018. This represents approximately 18 900 Islanders.[2]

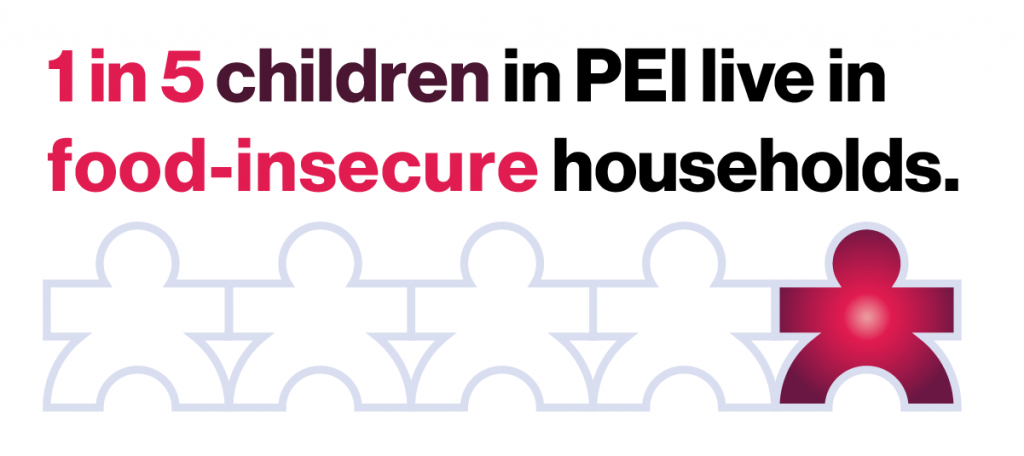

Households with children under 18 years old are more vulnerable to food insecurity than those without children. In PEI, 19.2% of children lived in food-insecure households. This means that almost 1 in 5 children in the province were in families who could not always afford the food they needed.[2]

Food insecurity is a very serious public health problem. It negatively impacts the health of both children and adults. Research has shown that the health effects of food insecurity go far beyond nutrition and include a wide range of physical and mental health problems.[3][4][5][6] This means food insecurity is also a costly problem for provinces and territories because the health care needs of people who are food insecure place a tremendous burden on our healthcare system.[7]

The need for income-based interventions to reduce food insecurity

The only intervention that has ever been shown to move the needle on food insecurity is income. Research has found reductions in food insecurity where federal or provincial policies have improved the financial circumstances of vulnerable households.[8][9][10]

To reach the target of eliminating food insecurity among children in the next 5 years, all the evidence points to enacting policies and programs that ensure families have enough money to make ends meet.[9][11][12]

There are many ways that provincial policies impact the adequacy and stability of families’ incomes, and therefore food insecurity . Provincial governments are responsible for social assistance, they set minimum wages and employment standards, they deliver social housing programs, they levy taxes and deliver tax credits, and many provide child benefits.

The key to reaching targets for food insecurity reductions are policies that impact households reliant on employment income. These households make up the majority (63.7%) of the food-insecure on the Island.[2] Households relying on low-wage jobs, part-time, temporary, or precarious work, or a single wage earner for multiple people are the most vulnerable.

Reductions in the provincial income tax rate for low-income households and increases to minimum wage could both help reduce food insecurity for these households.[13] PEI increased their minimum wage to $13 per hour earlier this month.[14]

A second important focus for provincial action to reduce food insecurity is social assistance. Across Canada, households relying on social assistance are very likely to be food-insecure. This is especially the case in PEI, where 85.6% of households relying on social assistance were food-insecure in 2017-2018.[2] Evidence from both British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador have demonstrated that improvements to social assistance can reduce food insecurity for these households.[8][15]

In a 2018 review of PEI’s social assistance, the Auditor General drew attention to the limited increases in assistance rates and delays in planned increases.[16] Since 2018, PEI has increased social assistance rates, income exemptions, and liquid asset exemptions, to provide those receiving social assistance with more income.[17][18][19]

Increases to minimum wage and social assistance incomes are steps in the right direction given what we know about the need for adequate incomes to reduce food insecurity. It remains to be seen how much these measures improve Islanders’ financial circumstances and affect food insecurity rates, but the new targets provide an important benchmark for assessing the impact and identifying next steps.

Lessons from Newfoundland and Labrador

The only time any jurisdiction has had a major decline in their rate of food insecurity over the past 16 years of monitoring was in Newfoundland and Labrador from 2007 to 2012. The province went from having the highest rate among the provinces in 2007 to having the lowest in 2011 and sustained some of its reductions in 2012.[8]

This decline followed the introduction of a new poverty reduction strategy, one that included eliminating and lowering provincial income taxes for the lowest and mid-low income households, increasing the minimum wage by $4 per hour over 4 years, increasing social assistance rates with indexation to inflation, and increasing liquid asset and income exemptions for social assistances recipients, among other initiatives.[20]

Unfortunately, the tremendous reduction in food insecurity that Newfoundland and Labrador achieved between 2007 and 2012 has not been sustained. In 2017-2018, after 4 years of not measuring food insecurity, Newfoundland and Labrador’s rate had risen substantially.[2] This shift highlights the importance of provinces continually monitoring their food insecurity rates, understanding how their policies and programs affect this problem, and maintaining the interventions that protect households from food insecurity.

An important step forward

PEI takes an important step forward by setting explicit targets for food insecurity reduction. These new targets hold the government accountable for re-evaluating the adequacy of existing supports and introducing new policies that allow all Islanders to make ends meet. Other provinces and territories should follow their lead and make legislative commitments to reducing food insecurity.

References

- Poverty Elimination Strategy Act. Bill 107, Prince Edward Island Legislative Assembly (66th General Assembly), 2nd session. 2021. Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/legislation/p-14-1-poverty_elimination_strategy_act.pdf

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017-2018 [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF); 2020. Available from: https://proof.utoronto.ca/resources/proof-annual-reports/household-food-insecurity-in-canada-2017-2018/

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L, McIntyre L. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. The Journal of Nutrition. 2013;143(11):1785–93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.178483

- McIntyre L, Wu X, Kwok C, Patten SB. The pervasive effect of youth self-report of hunger on depression over 6 years of follow up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(5):537–47. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1361-5

- Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM – Population Health. 2017;3:464–72. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352827316301410

- Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. Association between household food insecurity and mortality in Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2020;192(3):E53–60. Available from: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/3/E53

- Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with higher health care use and costs among Canadian adults. Health Affairs. 2020;39(8):1377–85. Available from: http://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01637

- Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007–2012. Canadian Public Policy. 2015;41(3):191–206. Available from: https://utpjournals.press/doi/10.3138/cpp.2014-080

- Brown EM, Tarasuk V. Money speaks: Reductions in severe food insecurity follow the Canada Child Benefit. Preventive Medicine. 2019;129. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743519303524

- McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C, Emery JCH. Reduction of food insecurity among low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income. Canadian Public Policy. 2016;42(3):274–86. Available from: https://utpjournals.press/doi/10.3138/cpp.2015-069

- Tarasuk V, Li N, Dachner N, Mitchell A. Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 2005–2014. Canadian Public Policy. 2019;45(1):93–104. Available from: https://utpjournals.press/doi/10.3138/cpp.2018-054

- Ionescu-Ittu R, Glymour MM, Kaufman JS. A difference-in-differences approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Preventive Medicine. 2015;70:108–16. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743514004605

- Men F, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. The role of provincial social policies and economic environments in shaping food insecurity among Canadian families with children. Preventive Medicine. 2021;148:106558. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743521001420

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Minimum Wage Order (Board and Lodging) [Internet]. Prince Edward Island. 2015;Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/economic-growth-tourism-and-culture/minimum-wage-order-board-and-lodging

- Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Preventive Medicine. 2016;93:151–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743516303048

- MacAdam J. Report to the Legislative Assembly 2018 [Internet]. Charlottetown, PE: Office of the Auditor General; 2018. Available from: https://www.assembly.pe.ca/sites/www.assembly.pe.ca/files/2018-AG-ar.pdf

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Social Assistance Renewal [Internet]. Prince Edward Island. 2018;Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/family-and-human-services/social-assistance-renewal. Accessed 2021-04-20.

- Government of Prince Edward Island. New initiatives to help all Islanders participate and thrive [Internet]. Prince Edward Island. 2018;Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/new-initiatives-help-all-islanders-participate-and-thrive. Accessed 2021-04-20.

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Social assistance rates increasing across the Island [Internet]. Prince Edward Island. 2019;Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/social-assistance-rates-increasing-across-the-island. Accessed 2021-04-20.

- Newfoundland and Labrador. Reducing poverty: an action plan for Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John’s, Nfld: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador; 2006. Available from: https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/205006

Commentary | Story

Prince Edward Island: The first jurisdiction to set explicit targets for reducing food insecurity

April 21, 2021

Map of PEI modified from NordNordWest under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Earlier this month, MLAs in PEI unanimously passed the first bill in Canada that sets explicit and binding targets for food insecurity reduction. The Poverty Elimination Strategy Act, tabled by Green MLA Hannah Bell, establishes targets for reducing the rates of poverty, food insecurity, and chronic homelessness on the Island.[1]

By passing this bill, the government commits to eliminating food insecurity among children and halving the provincial rate of food insecurity by 2025. The goal is to eliminate food insecurity in PEI entirely by 2030.[1]

Targets established by the Poverty Elimination Strategy Act[1]

By 2025:

By 2030:

By 2035:

While federal, provincial, and territorial governments have all committed to poverty reduction strategies, only some have any specific, measurable targets (Federal, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and now PEI). Other than PEI, none have declared food insecurity reduction targets or commitments to fully eliminate poverty.

The next steps for PEI should be to re-evaluate their poverty reduction plans and ensure that the actions taken are evidence-based and move them towards these targets.

Statistics Canada measures food insecurity using the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) on the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The HFSSM consists of 18 questions about the experiences of food insecurity, ranging from worrying about running out of food to going whole days without eating, due to financial constraint.

Food insecurity in PEI

Based on the most recently available data, 14.0% of households in PEI were food-insecure in 2017-2018. This represents approximately 18 900 Islanders.[2]

Households with children under 18 years old are more vulnerable to food insecurity than those without children. In PEI, 19.2% of children lived in food-insecure households. This means that almost 1 in 5 children in the province were in families who could not always afford the food they needed.[2]

Food insecurity is a very serious public health problem. It negatively impacts the health of both children and adults. Research has shown that the health effects of food insecurity go far beyond nutrition and include a wide range of physical and mental health problems.[3][4][5][6] This means food insecurity is also a costly problem for provinces and territories because the health care needs of people who are food insecure place a tremendous burden on our healthcare system.[7]

The need for income-based interventions to reduce food insecurity

The only intervention that has ever been shown to move the needle on food insecurity is income. Research has found reductions in food insecurity where federal or provincial policies have improved the financial circumstances of vulnerable households.[8][9][10]

To reach the target of eliminating food insecurity among children in the next 5 years, all the evidence points to enacting policies and programs that ensure families have enough money to make ends meet.[9][11][12]

There are many ways that provincial policies impact the adequacy and stability of families’ incomes, and therefore food insecurity . Provincial governments are responsible for social assistance, they set minimum wages and employment standards, they deliver social housing programs, they levy taxes and deliver tax credits, and many provide child benefits.

The key to reaching targets for food insecurity reductions are policies that impact households reliant on employment income. These households make up the majority (63.7%) of the food-insecure on the Island.[2] Households relying on low-wage jobs, part-time, temporary, or precarious work, or a single wage earner for multiple people are the most vulnerable.

Reductions in the provincial income tax rate for low-income households and increases to minimum wage could both help reduce food insecurity for these households.[13] PEI increased their minimum wage to $13 per hour earlier this month.[14]

A second important focus for provincial action to reduce food insecurity is social assistance. Across Canada, households relying on social assistance are very likely to be food-insecure. This is especially the case in PEI, where 85.6% of households relying on social assistance were food-insecure in 2017-2018.[2] Evidence from both British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador have demonstrated that improvements to social assistance can reduce food insecurity for these households.[8][15]

In a 2018 review of PEI’s social assistance, the Auditor General drew attention to the limited increases in assistance rates and delays in planned increases.[16] Since 2018, PEI has increased social assistance rates, income exemptions, and liquid asset exemptions, to provide those receiving social assistance with more income.[17][18][19]

Increases to minimum wage and social assistance incomes are steps in the right direction given what we know about the need for adequate incomes to reduce food insecurity. It remains to be seen how much these measures improve Islanders’ financial circumstances and affect food insecurity rates, but the new targets provide an important benchmark for assessing the impact and identifying next steps.

Lessons from Newfoundland and Labrador

The only time any jurisdiction has had a major decline in their rate of food insecurity over the past 16 years of monitoring was in Newfoundland and Labrador from 2007 to 2012. The province went from having the highest rate among the provinces in 2007 to having the lowest in 2011 and sustained some of its reductions in 2012.[8]

This decline followed the introduction of a new poverty reduction strategy, one that included eliminating and lowering provincial income taxes for the lowest and mid-low income households, increasing the minimum wage by $4 per hour over 4 years, increasing social assistance rates with indexation to inflation, and increasing liquid asset and income exemptions for social assistances recipients, among other initiatives.[20]

Unfortunately, the tremendous reduction in food insecurity that Newfoundland and Labrador achieved between 2007 and 2012 has not been sustained. In 2017-2018, after 4 years of not measuring food insecurity, Newfoundland and Labrador’s rate had risen substantially.[2] This shift highlights the importance of provinces continually monitoring their food insecurity rates, understanding how their policies and programs affect this problem, and maintaining the interventions that protect households from food insecurity.

An important step forward

PEI takes an important step forward by setting explicit targets for food insecurity reduction. These new targets hold the government accountable for re-evaluating the adequacy of existing supports and introducing new policies that allow all Islanders to make ends meet. Other provinces and territories should follow their lead and make legislative commitments to reducing food insecurity.

References