Food Insecurity Measurement in Canada: Interpreting the Statistics

February 8, 2017

This webinar is part 1 of a 3-part series in collaboration with Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada (CDPAC). It discusses how household food insecurity is monitored and reported in Canada, and how to accurately and effectively use the data.

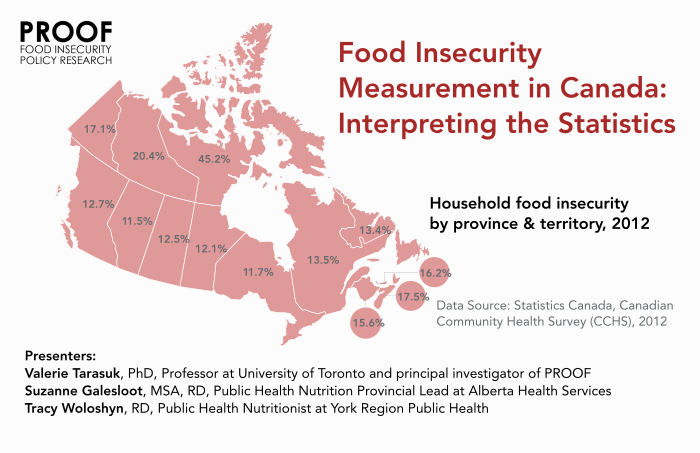

Food insecurity — the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints — is increasingly recognized as a serious public health problem. Since 2005, household food insecurity has been systematically monitored in Canada through the Canadian Community Health Survey run by Statistics Canada.

The growing use of these data by public health, community agencies, research centres, and social policy groups has been critical in building awareness and understanding of the problem of food insecurity. However, inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the reporting of data on food insecurity mask the scale and severity of this problem.

The accurate and effective use of Canada’s monitoring data hinges on a clear understanding of what exactly is being measured on the Canadian Community Health Survey, what it means, and how to interpret the food insecurity statistics available on Statistics Canada’s website (CANSIM).

This webinar is part 1 of a 3-part series in collaboration with Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada (CDPAC). See part 2, Who is vulnerable to household food insecurity and what does this mean for policy and practice?, and part 3, How does food insecurity relate to health and what are the implications for health care providers?.

Presenters:

Valerie Tarasuk, PhD — Professor, University of Toronto

Suzanne Galesloot, MSA, RD — Public Health Nutrition Provincial Lead, Alberta Health Services

Tracy Woloshyn, RD — Public Health Nutritionist, York Region Public Health

Resources:

Webinar Slides [PDF]

ODPH Position Statement on Responses to Food Insecurity (formerly OSNPPH)

Research publications mentioned:

Cox, J., Hamelin, A. M., McLinden, T., Moodie, E. E., Anema, A., Rollet-Kurhajec, K. C., … & Canadian Co-infection Cohort Investigators. (2016). Food insecurity in HIV-hepatitis C virus co-infected individuals in Canada: the importance of co-morbidities. AIDS and Behavior, 1-11.