What can be done to reduce food insecurity in Canada?

There is a strong body of evidence showing that food insecurity can be reduced through policy interventions that improve the incomes of low-income households. This page summarizes this evidence and discusses why governments must focus on addressing inadequate incomes to reduce food insecurity, instead of funding food charity.

Research has repeatedly shown that household food insecurity can be reduced by policy interventions that improve the financial circumstances of households at the bottom of the income spectrum.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] When food-insecure households receive additional income, they spend it in ways that improve their food security.

We’ve examined the impact of numerous provincial and federal policies on food insecurity in Canada, including our public pension system and changes to social assistance, child benefits, and minimum wage.

None of these policy interventions were explicitly designed to address household food insecurity, but they had impacts on this problem because they improved households’ financial circumstances. Some of these policy interventions would likely have had an even stronger effect on household food insecurity rates if they targeted more resources to at-risk groups.

Food insecurity research tells us that our public policies have left low-income Canadians, particularly working age adults and their families, behind for a long time. The persistence of high rates of food insecurity is a clear sign that there needs to be a dedicated effort to restructure federal, provincial, and territorial policies to target food insecurity reduction and ensure Canadians have enough money for basic needs.

Federal Policies That Reduce Food Insecurity

Public Old-Age Pensions

Canada’s public pension programs for seniors are a prime example of how policies can reduce food insecurity by improving the stability and adequacy of households’ income.

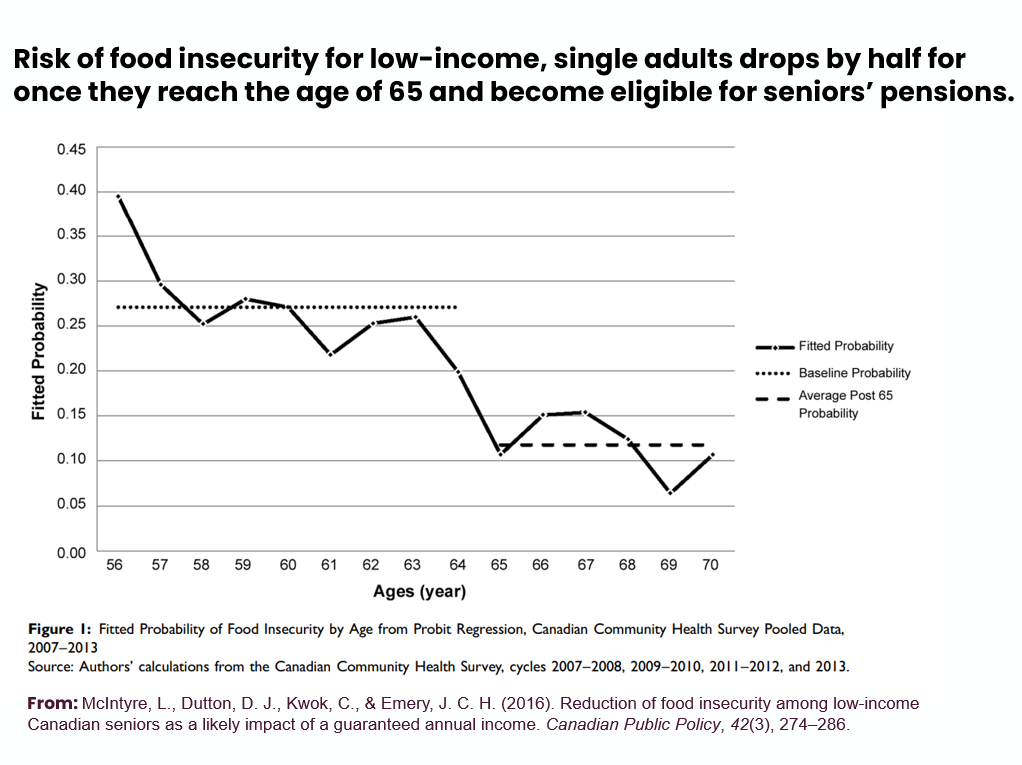

It has long been known that households reliant on seniors’ pensions and retirement incomes have the lowest rate of food insecurity in Canada,[8] but our research has gone further to show that the risk of food insecurity for low-income, unattached adults is cut in half once they become eligible for these programs at age 65 (i.e. Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement, and Canada Pension Plan/Quebec Pension Plan).[7]

Although the income provided through these pension programs is still low, it is well above the amount these individuals would’ve received through social assistance programs. It is also reliable, allowing recipients to better manage income shocks. And, public pensions are indexed to inflation.

These findings highlight the protective effect of our public pension system on the food security of Canadian seniors and the inadequacy of other income support programs for low-income, working age adults. They also point to the potential of an income floor to protect Canadians from food insecurity and lend support to calls for a Basic Income program as an anti-poverty intervention.

Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

The Canada Child Benefit (CCB) is a federal income supplement program that supports households with children under 18. It is a key component of the federal poverty reduction strategy. Our study of the implementation of the CCB showed that it had an impact on food insecurity among households with children, but it could’ve gone further by targeting more funds to the lowest income families.[1]

Although there wasn’t reduction in the overall prevalence of food insecurity among families with children following the introduction of the CCB, the prevalence of severe food insecurity among low-income families dropped by a third.[1] The reduction in severe food insecurity is important considering that severe food insecurity is very strongly associated with serious negative health outcomes.

These findings highlight how modest income supplements can reduce food insecurity, with the largest effect being for lowest-income families — those most likely at risk for food insecurity – and severe food insecurity, in particular. They also reinforce the need to design policies with this outcome in mind in order to maximize their potential.

Our understanding of the effect of the CCB on food insecurity is consistent with other research results. A study of the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB), the predecessor of the CCB, had similar findings that demonstrated the impact of child benefits on food insecurity.[2]

International research comparing 142 countries also found that the risk of food insecurity among households with children was lower in countries with public financial supports for families.[9] The impact of these policies was greatest among low-income families.

Provincial/Territorial Policies That Reduce Food Insecurity

Differences in the prevalence of household food insecurity across the provinces and territories highlight the critical role that provincial and territorial policies can play in reducing household food insecurity in Canada.

The decisions these governments make on policies like minimum wage, social assistance, income tax, child benefits, and other income supports directly determine households’ incomes and therefore, their food security.

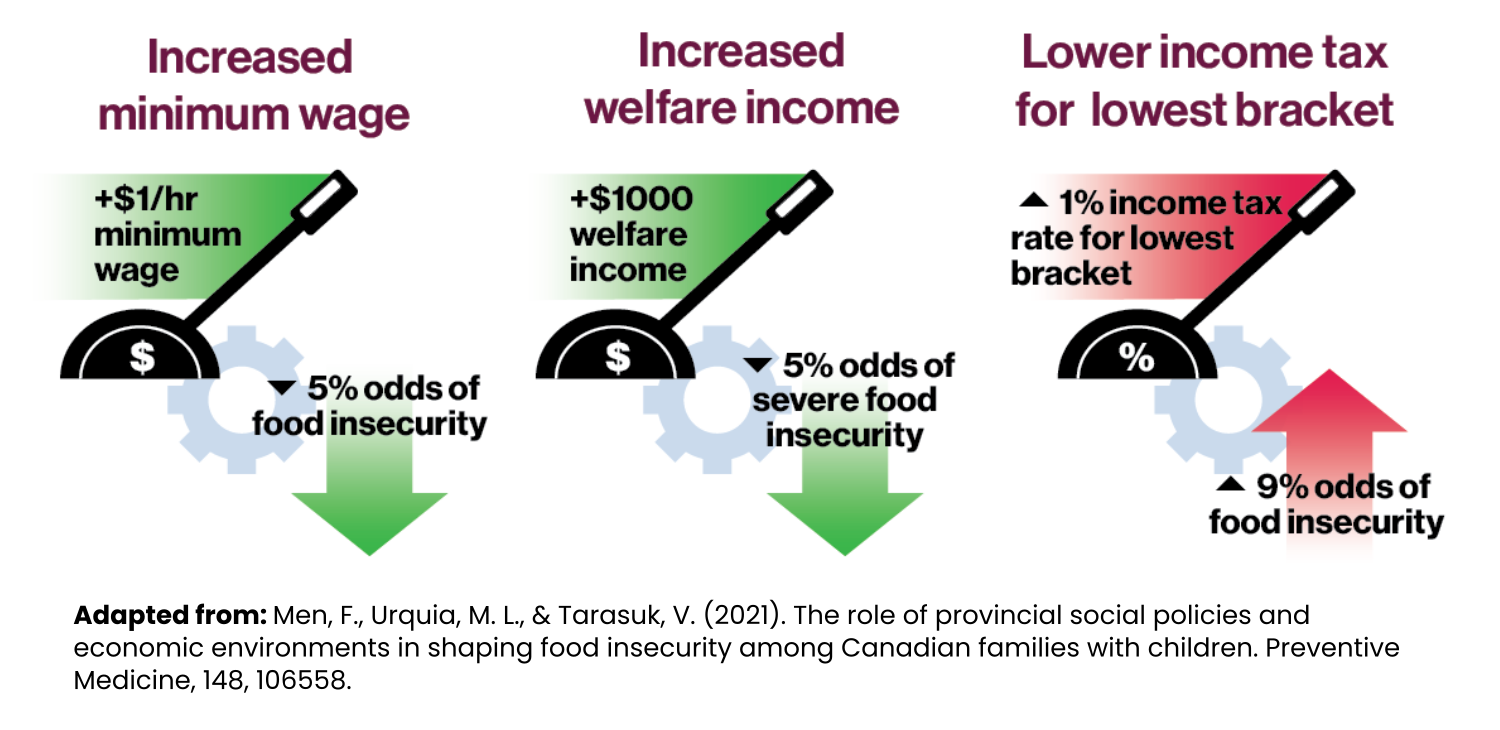

Our examination of social policies across the provinces determined that increases to the minimum wage, increase welfare incomes, and lower income taxes for low-income households reduce the risk of food insecurity.[3] Our research has also charted reductions in food insecurity among recipients of social assistance increases and new child benefits.[4][5][6]

Social Assistance

Social assistance programs vary among provinces and territories but being on social assistance anywhere in Canada poses an extremely high risk of food insecurity.[10] The current design of social assistance programs sees the majority of households relying on them unable to make ends meet.

Our research has shown that a $1000 increase in annual welfare income is associated with 5% lower odds of severe food insecurity.[3] Severe food insecurity is far more prevalent among households relying on social assistance.

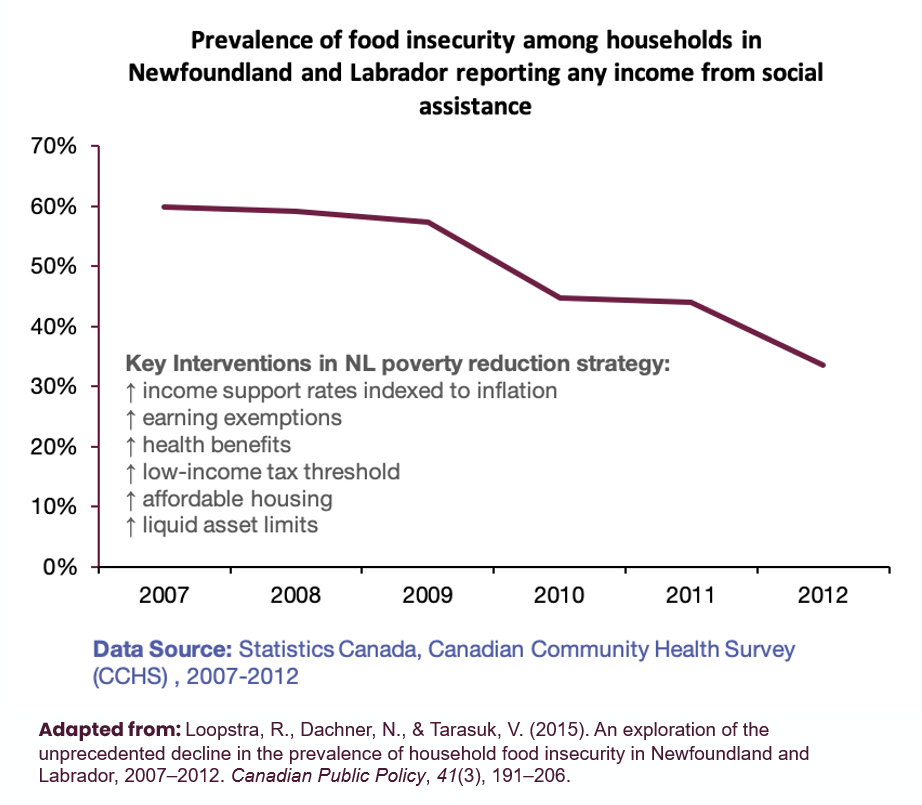

The various improvements to social assistance introduced by the 2006 Newfoundland and Labrador Poverty Reduction Strategy led to drastic declines in food insecurity among social assistance recipients.[6] Those declines were a major part of the unprecedented 5 percentage point decrease in the provincial prevalence of food insecurity observed between 2007 and 2011.

A one-time increase in welfare incomes in British Columbia in 2007 was associated with a reduction in food insecurity among this highly vulnerable group.[4] However, the impact was short-lived and returned to previous levels by 2012, potentially due to the lack of indexation of the rate to inflation.

Only 3 provinces and territories currently index their support rates to inflation (New Brunswick, Quebec, Yukon). The recent record inflation levels have drawn attention to the importance of indexation as part of the design of social assistance to ensure benefits aren’t eroded by inflation. However, benefit levels must also be made higher everywhere if they are to be sufficient to protect recipients from food insecurity.

Minimum Wage

Addressing the inadequacy of wages in Canada is an important part of tackling food insecurity because the majority of food-insecure households are in the workforce.[10] The workers most likely to report food insecurity are those with low-wage, short-term or precarious jobs, racialized workers, those working multiple jobs, and those providing for multiple people with a single income.[11]

Increasing the minimum wage is one way that provincial governments can reduce household food insecurity for low-income workers and their families. Our research on food insecurity rates in the provinces has shown that a one-dollar increase in minimum wage was associated with 5% lower odds of experiencing food insecurity.[3]

Research comparing food insecurity across 139 countries also found that working adults in countries with higher minimum wage or collective bargaining are less likely to be food-insecure.[12] This effect was strongest for full-time workers, but still applied to part-time workers.

The potential for higher minimum wages to trigger increases in unemployment is a commonly cited reason to not raise the minimum wage. While higher unemployment is associated with increased food insecurity, research suggests that the benefit of a higher minimum wage for food insecurity reduction outweighs the impact of any consequent unemployment.[12]

In addition to raising minimum wages, provinces should also work towards stronger income supports for the precariously employed or unemployed, better employment standards, more support for collective bargaining, measures to combat racism in the labour market, and more job opportunities, as part of a strategy to reduce food insecurity.

One of the success stories of food insecurity reduction in Canada comes from Newfoundland and Labrador between 2007 and 2012. The province saw unprecedented declines in the prevalence of food insecurity following the introduction of a new poverty reduction strategy in 2006, which targeted the depth of poverty through a wide range of interventions.[6]

Although not explicitly designed to address food insecurity, the strategy had a substantial impact by improving households’ financial circumstances through interventions like eliminating and lowering provincial income taxes for the lowest and mid-low-income households, increasing the minimum wage by $4 per hour over 4 years, increasing social assistance rates with indexation to inflation, and increasing liquid asset and income exemptions for social assistances recipients, among others.

Many of these policies were geared towards improving social assistance and brought recipients out of food insecurity. Between 2007 and 2012, the prevalence of food insecurity among social assistance recipients in Newfoundland and Labrador decreased by almost half. This decline accounted for 44% of the overall provincial decline over those years.

Because food insecurity captures deprivation differently from conventional income-based measures of poverty, changes in provincial poverty rates do not necessarily translate into changes in food insecurity prevalence, and vice versa. This decline in food insecurity that occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador for example, is much sharper than any change in low-income rates reported by the province over that period.

Unfortunately, Newfoundland and Labrador elected not to measure household food insecurity on the CCHS in the two survey cycles after 2012. Many political and economic changes had occurred since then, like the end of indexing benefits to inflation in 2012.

By the time there were statistics on food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador again in 2017-2018, food insecurity had returned to concerning levels.[13] This situation reminds us that food insecurity is sensitive to policy changes for the better or worse and stresses the need to assess the effects of changes on food insecurity in an ongoing way.

Policy action to date has not sought to reduce food insecurity in any concerted, evidence-based way.

Addressing household food insecurity as a problem of inadequate incomes has garnered little policy traction, despite there being decades of measurement and research.

Although household food insecurity has been included as an indicator on the federal Poverty Reduction Strategy and mentioned in several provincial and territorial poverty reduction strategies, it has not been an explicit focus of these strategies, nor has their impact on food insecurity been evaluated as part of the policy making process.

Important next steps are for governments to legislate targets for food insecurity reduction and evaluate policy interventions against this outcome as part of deliberate and coordinated plans to reduce food insecurity.

P.E.I is the first and only jurisdiction to have legislated targets through their 2021 Poverty Elimination Act. The act sets a timetable for reducing the prevalence of food insecurity and provides a way to hold the government accountable for evaluating the adequacy of existing supports and introduce new policies that ensure all Islanders can make ends meet. A similar bill was recently introduced in Nova Scotia.[14] However, targeted policy actions to reduce food insecurity remain elusive, while public funding for food charity initiatives grows.

Through research examining transcripts of provincial and federal parliamentary discussions over the period of 1995–2012, it is clear that Canada’s elected officials have long recognized that household food insecurity is caused by inadequate income.[15] However, they have remained focused on food banks and other food programs and sometimes linked food insecurity with unrelated policies around food safety and labelling.

The legislation that has been passed related to food insecurity has narrowly focused on food charity.[16] For example, there are now “Good Samaritan” laws absolving corporate donors of liability for the safety of donated food in every province and territory, and several provinces have implemented tax credits for local producers who donate unsold food to community agencies.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw federal and provincial governments launch unprecedented investments of public funds into food charity as their policy response to food insecurity.[17][18][19][20][21][22] The Auditor General’s recent review of the federal initiatives highlighted the absence of evidence that they had achieved the intended outcome of reducing food insecurity.[23]

Provinces have also continued funding food banks and other community food initiatives in response to the record high rates of inflation in late 2021 and 2022.[24][25][26][27]

Government funding of food charity is ill-founded and further entrenches an ineffective response for reducing household food insecurity.

Canada has a long history of food charity that has led to a massive network of non-profit food providers.[28] This network has grown even larger through the pandemic.

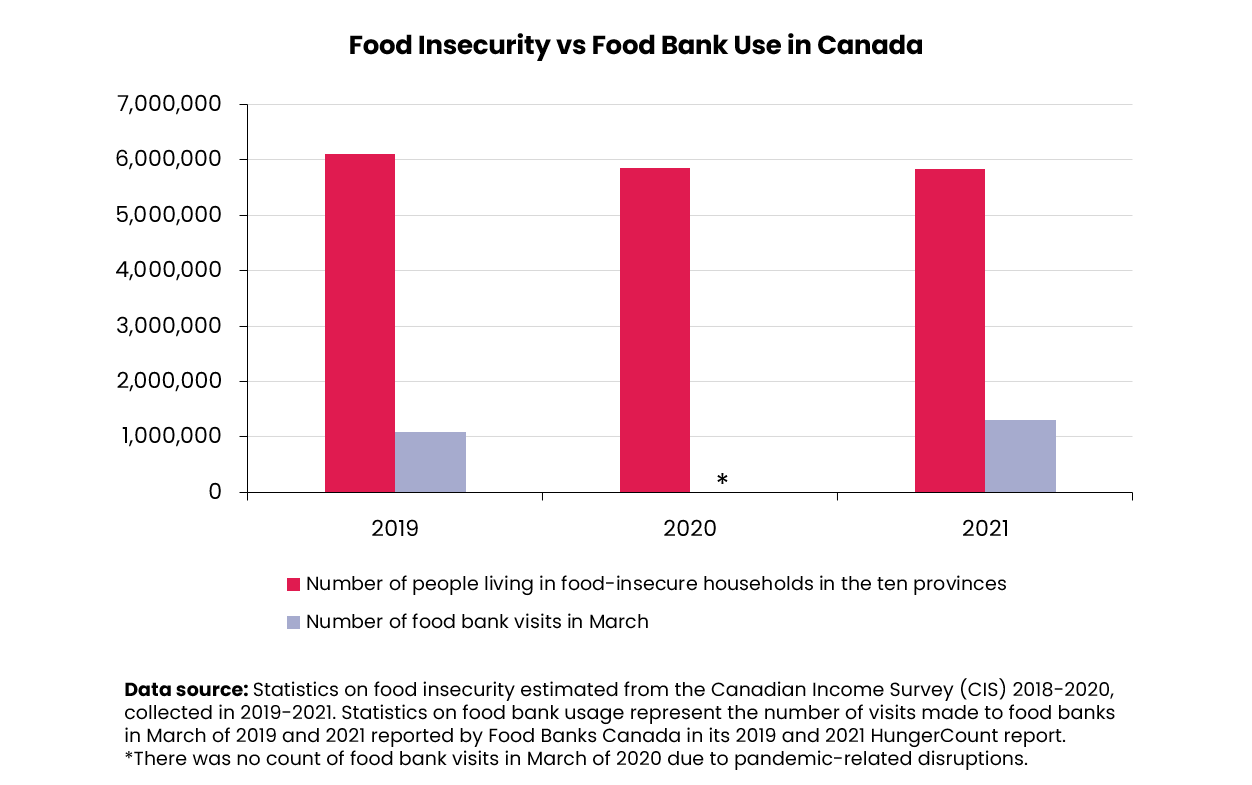

However, food insecurity monitoring shows that there has been no meaningful progress in reducing household food insecurity despite these efforts. A comparison of the national statistics also indicates there is a substantial and persistent disconnect between the number of people living in food-insecure households versus those accessing food banks.

The profound disconnect between food insecurity statistics and food bank numbers is consistent with studies of the coping strategies of food-insecure Canadians. A 2019 study found that food bank use was one of the least common strategies used by food-insecure households to manage their resources when short on funds.[29] These households were much more likely to ask for financial help from friends or family and to miss bill payments. This suggests that most people who are struggling with severe food insecurity do not see food banks as a solution to their problem.

While visiting food banks may provide temporary food relief for those who use them, food banks are unable to address the serious financial hardships that give rise to food insecurity. There is no evidence that food charity can move households out of food insecurity, with studies repeatedly showing that food bank visitors remain food-insecure despite food bank use.[29][30][31][32]

There is also no evidence that other kinds of food-based programs like food literacy education, alternative food retail, food prescriptions, or community gardens can move households out of food insecurity.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

Research has repeatedly shown that food insecurity is not associated with food skills.[33][36][37] These findings challenge the notion that households are food-insecure because they lack food skills and that this problem can be resolved by programs intended to improve them. In fact, most Canadians consider themselves skilled at food preparation, regardless of food insecurity status.[40]

Given the scale of the problem and the need to address income inadequacy, governments’ continued focus on funding food charity and other food-based initiatives as a response to food insecurity is ill-founded. It should stop in favor of policies that better support household incomes.

Food insecurity in Nunavut remains a massive problem despite continued investments in Nutrition North Canada.

Household food insecurity in Nunavut has been at exceptionally high rates for as long as there has been monitoring of this problem. Nutrition North Canada is a federal food subsidy introduced in 2011 to improve food access in remote Northern communities by subsidizing the cost of transporting perishable, nutritious foods. Multiple analyses of household food insecurity in Nunavut revealed that it had gotten worse following the introduction of the program.[41][42]

More recent data from the Canadian Income Survey suggest that the situation in this territory remains dire. The CIS data available for Nunavut collected in 2020 do not include marginal food insecurity, but 46.1% of people in Nunavut were living in moderately or severely food-insecure households that year.[43] Half of these people (23.3% of Nunavut’s population) lived in a severely food-insecure household.

These findings raise serious questions around the federal government’s continued focus on food subsidies and highlight the need for more effective initiatives to address food insecurity in the North. They also echo long-standing concerns from Inuit organizations, community groups, and Senators.

A recent report by the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs called on the government to recognize that food insecurity cannot be solved by the Nutrition North Canada program and to work with Inuit peoples towards Inuit-led reformation of the program and poverty reduction initiatives.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national representative organization for Inuit in Canada, recently released their Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy. It lays out a plan for Inuit-led food security and poverty reduction initiatives and calls for concerted policy action guided by Inuit engagement, such as the reformation of Nutrition North Canada as a food security program. It also outlines the importance of consistent Inuit-led monitoring and research on food insecurity for evaluating the impact of interventions and informing decision-making.

There is wide consensus for income-based responses to household food insecurity.

While food banks, mutual aid groups, and other civil society organizations continue to do their best to help those in need, they also recognize that they cannot solve food insecurity. They are joined by public health organizations, anti-poverty advocates, and other groups in calling for federal and provincial governments to take action through income-based interventions.

Some position statements and policy recommendations on income-based interventions to food insecurity

Alberta Policy Coalition for Cancer Prevention

Association of Local Public Health Agencies

Campaign 2000

Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada

Community Food Centres Canada

Daily Bread Food Banks

Diabetes Canada

Dietitians of Canada

Feed Ontario

Food Banks Canada

Food First NL

FoodShare TO

Food Secure Canada

Greater Ontario Food Collective

Ontario Basic Income Network

Ontario Dietitians in Public Health

Reducing household food insecurity requires the commitment of public revenue and resources to ensure that income supports for low-income, working-aged Canadians and their families are adequate, secure, and responsive to changing costs of living, irrespective of their income source.

References

- Brown E, Tarasuk V. Money speaks: Reductions in severe food insecurity follow the Canada Child Benefit. Prev Med. 2019;129:105876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105876

- Ionescu-Ittu R, Glymour M, Kaufman J. A difference-in-difference approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Preventive Medicine. 2015;70:108-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.017

- Men F, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V. The role of provincial social policies and economic environment in shaping household food insecurity among families with children in Canada. Preventive Medicine. 2021;148:106558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106558

- Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005-2012. Preventive Medicine. 2016;93:151-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.002

- Tarasuk V, Li N, Dachner N, et al. Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 2005-2014. Canadian Public Policy. 2019;45(1):93-104. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2018-054

- Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007-2012. Canadian Public Policy. 2015;41(3):191-206. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2014-080

- McIntyre L, Dutton D, Kwok C, et al. Reduction of food insecurity in low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a Guaranteed Annual Income. Canadian Public Policy. 2016;42(3):274-86. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2015-069

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2011. Toronto ON: Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF); 2013. https://proof.utoronto.ca/resource/household-food-insecurity-in-canada-2011/

- Reeves A, Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. Family policy and food insecurity: an observational analysis in 142 countries. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2021;5:e506-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00151-0

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF); 2022. https://proof.utoronto.ca/resource/household-food-insecurity-in-canada-2021/

- McIntyre L, Bartoo AC, Emery JC. When working is not enough: food insecurity in the Canadian labour force. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):49-57. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980012004053

- Reeves A, Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. Wage setting policies, employment, and food insecurity : a multilevel analysis of 492,078 people in 139 countries. American Journal of Public Health. 2021;111(4):718-25. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.306096

- Hussain Z, Tarasuk V. A comparison of household food insecurity rates in Newfoundland and Labrador in 2011–2012 and 2017–2018. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2022;113(2):239-49. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00577-6

- Nova Scotia House of A. Bill 169 – Poverty Elimination Act. Nova Scotia Legislature. 2022. https://nslegislature.ca/legc/bills/64th_1st/1st_read/b169.htm

- McIntyre L, Patterson P, Anderson L, et al. Household food insecurity in Canada: problem definition and potential solutions in the public policy domain. Canadian Public Policy. 2016;42(1):83-93. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2015-066

- McIntyre L, Lukic R, Patterson P, et al. Legislation debated as responses to household food insecurity in Canada, 1995-2012. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. 2016;11(4):441-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2016.1157551

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Local Food Infrastructure Fund: Applicant guide. 2019. [updated 2019-08-15]. Available from: https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/local-food-infrastructure-fund/applicant-guide.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Emergency Food Security Fund. 2021. [updated 2021-12-22]. Available from: https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/emergency-food-security-fund.

- Office of the Premier. Ontario Protecting the Most Vulnerable During COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. [updated March 23, 2020]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56433/ontario-protecting-the-most-vulnerable-during-covid-19-crisis.

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Province supporting B.C.’s food banks during COVID-19. 2020. [updated March 29, 2020]. Available from: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2020MAH0049-000583.

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Provincial Government Partnering with Community to Support Food Sharing Programs. 2020. [updated March 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2020/exec/0325n04/.

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. COVID-19 – Une aide financière d’urgence de 2 M$ est octroyée aux Banques alimentaires du Québec – Salle de presse – MSSS. 2020. [updated March 24, 2020]. Available from: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/ministere/salle-de-presse/communique-2071/.

- Auditor General of Canada. COVID-19 Pandemic. Protecting Canada’s Food System. 2021. Contract No.: 12.

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Province provides $900,000 to Island food banks and home heating program. 2022. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/province-provides-900000-to-island-food-banks-and-home-heating-program

- Government of Nova Scotia. Government Invests in New Food Bank. News Releases. 2022. https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20220316006

- Government of New Brunswick. REVISED / Investment of $20 million to assist low-income individuals, families and seniors. 2022. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2022.06.0286.html

- Social Development Poverty Reduction. New provincial funding supports food security. 2022. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022SDPR0037-000843

- Nikkel L, Summerhill V, Gooch M, et al. Canada’s Invisible Food Network. Ontario, Canada: Second Harvest and Value Chain Management International; 2021 2021. https://www.secondharvest.ca/getmedia/b8cf1995-ec2a-4a13-9c3d-0a9d9b97beb0/Canada-s-Invisible-Food-Network.pdf

- Tarasuk V, Fafard St-Germain AA, Loopstra R. The relationship between food banks and food insecurity: insights from Canada. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2019;31(5):841-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00092-w

- Enns A, Rizvi A, Quinn S, et al. Experiences of food bank access and food insecurity in Ottawa, Canada. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. 2020;15(4):456-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2020.1761502

- Holmes E, Black J, Heckelman A, et al. “Nothing is going to change three months from now”: a mixed methods characterization of food bank use in Greater Vancouver. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;200:129-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.029

- Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. The relationship between food banks and household food insecurity among low-income Toronto families. Canadian Public Policy. 2012;38(4):497-514. https://doi.org/10.3138/CPP.38.4.497

- Huisken A, Orr S, Tarasuk V. Adults’ food skills and use of gardens are not associated with household food insecurity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;107(6):e526–e32. https://doi.org/10.17269%2FCJPH.107.5692

- Kirkpatrick S, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity and participation in community food programs among low-income Toronto families. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2009;100(2):135-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405523

- Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. Perspectives on community gardens, community kitchens and the Good Food Box program in a community-based sample of low-income families. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2013;104(1):e55-e9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405655

- Blanchet R, Loewen OK, Godrich SL, et al. Exploring the association between food insecurity and food skills among school-aged children. Public Health Nutrition. 2020;23(11):2000-5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004300

- Pepetone A, Vanderlee L, White CM, et al. Food insecurity, food skills, health literacy and food preparation activities among young Canadian adults: a cross-sectional analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(9):2377-87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000719

- Little M, Rosa E, Heasley C, et al. Promoting Healthy Food Access and Nutrition in Primary Care: A Systematic Scoping Review of Food Prescription Programs. American journal of health promotion : AJHP. 2021;36(3):518-36. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F08901171211056584

- Miewald C, Holben D, Hall P. Role of a Food Box Program: In Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Food Security. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2012;73(2):59-65. https://doi.org/10.3148/73.2.2012.59

- Orr S, Dachner N, Frank L, et al. The relationship between household food insecurity and infant feeding practices among Canadian mothers. CMAJ. 2018;190(11):E312-E9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170880

- Fafard St-Germain AA, Galloway T, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity in Nunavut following the introduction of Nutrition North Canada. CMAJ. 2019;191(20):E552-E8. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.181617

- Watson B, Daley A, Pandey S, et al., editors. From the Food Mail Program to Nutrition North Canada: The Impact on Food Insecurity among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Families with Children. 37th IARIW General Conference; 2022 2022.

- Caron N, Plunkett-Latimer J. Canadian Income Survey: Food insecurity and unmet health care needs, 2018 and 2019. Statistics Canada; 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2021009-eng.htm