In our new commentary, “Moment of reckoning for household food insecurity monitoring in Canada“, published in Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, we discuss the future of monitoring now that food insecurity is regularly measured on two Statistics Canada surveys, the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) and the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS).

The commentary aims to answer the question, which survey vehicle should be used to determine national, provincial, and territorial prevalence estimates?

At this crossroads, we recommend that the CIS be used as the tool for all food insecurity monitoring moving forward, for the following reasons.

- Since the CIS has a higher response rate than the CCHS (meaning more of the people it is intended to reach have responded to it), we believe that it provides more population representative estimates for food insecurity than CCHS. The CIS documents higher rates of food insecurity over similar periods and it is essential that Canada does not systematically underestimate food insecurity

- The CIS ensures consistent, annual measurement of household food insecurity, which is not the case through the CCHS because some jurisdictions opted out of monitoring food insecurity in years when it wasn’t mandatory.

- Data from the CIS is released publicly on a regular basis through Statistics Canada Data Tables and the reporting of the percentage of people living in moderately/severely food-insecure households on the Official Poverty Dashboard. The timely public releases better supports data access and policy-making.

- The CIS is designed to collect data about Canadians’ household financial circumstances. Monitoring food insecurity through this survey supports policy analyses and advances in identifying and designing effective policy interventions.

The CCHS has been invaluable for research into the health and healthcare implications of food insecurity in Canada and enabled systematic monitoring of food insecurity since 2005. The CIS now advances monitoring by providing reliable, annual, national measurement of food insecurity. It should be what federal, provincial, and territorial governments use to track the problem, set targets, evaluate programs, and identify priorities for policy intervention.

Critically, the analysis provided in this commentary raises serious questions about previous descriptions of lower rates of food insecurity using data from CCHS, given the very low response rate of CCHS 2020.

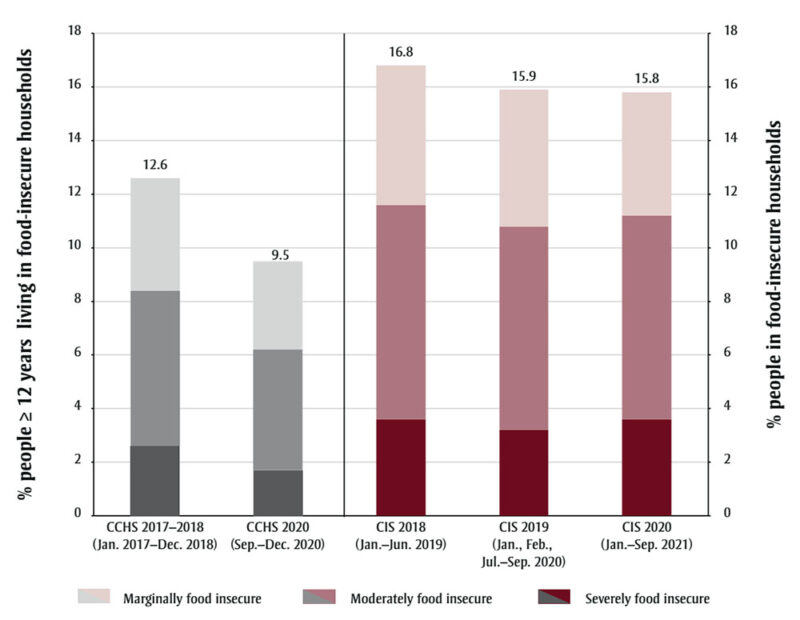

Percentage of people living in food-insecure households in Canada, excluding the territories

Sources: CCHS data are from Polsky and Garriguet (2022) and CIS data are from Statistics Canada (2022). The survey year for CCHS refers to the year of interview, whereas survey year for CIS refers to the year prior to the year of interview. The survey collection periods are indicated in parentheses. Food insecurity is assessed over the prior 12 months.

Please note there are differences between the statistics in this commentary and other sources like our 2021 report, such as the unit of measurement for food insecurity (reported as percentage of people living in food-insecure households in the commentary). The differences between estimates from the CIS and CCHS and differences in ways these data are reported in different places are described in further detail in “How is food insecurity measured in Canada?” p8-10 of Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021.

Commentary | Research

Moment of reckoning for household food insecurity monitoring in Canada

October 13, 2022

In our new commentary, “Moment of reckoning for household food insecurity monitoring in Canada“, published in Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, we discuss the future of monitoring now that food insecurity is regularly measured on two Statistics Canada surveys, the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) and the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS).

The commentary aims to answer the question, which survey vehicle should be used to determine national, provincial, and territorial prevalence estimates?

At this crossroads, we recommend that the CIS be used as the tool for all food insecurity monitoring moving forward, for the following reasons.

The CCHS has been invaluable for research into the health and healthcare implications of food insecurity in Canada and enabled systematic monitoring of food insecurity since 2005. The CIS now advances monitoring by providing reliable, annual, national measurement of food insecurity. It should be what federal, provincial, and territorial governments use to track the problem, set targets, evaluate programs, and identify priorities for policy intervention.

Critically, the analysis provided in this commentary raises serious questions about previous descriptions of lower rates of food insecurity using data from CCHS, given the very low response rate of CCHS 2020.

Percentage of people living in food-insecure households in Canada, excluding the territories

Sources: CCHS data are from Polsky and Garriguet (2022) and CIS data are from Statistics Canada (2022). The survey year for CCHS refers to the year of interview, whereas survey year for CIS refers to the year prior to the year of interview. The survey collection periods are indicated in parentheses. Food insecurity is assessed over the prior 12 months.

Read the full commentary, Moment of reckoning for household food insecurity monitoring in Canada

Please note there are differences between the statistics in this commentary and other sources like our 2021 report, such as the unit of measurement for food insecurity (reported as percentage of people living in food-insecure households in the commentary). The differences between estimates from the CIS and CCHS and differences in ways these data are reported in different places are described in further detail in “How is food insecurity measured in Canada?” p8-10 of Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021.