This article on the need to shift away from food bank statistics for discussing food insecurity was written for Upstream‘s series focused on food insecurity in Canada.

‘Food insecurity’ refers to the inadequate access to food because of financial constraints — and it’s a larger problem in Canada than most realize.

Since 1997 Food Banks Canada has released annual reports called ‘Hunger Count’ documenting the food bank usage. These reports have received wide media attention and are now a common point of reference when we discuss Canadian food insecurity, but they barely scratch the surface of the problem.

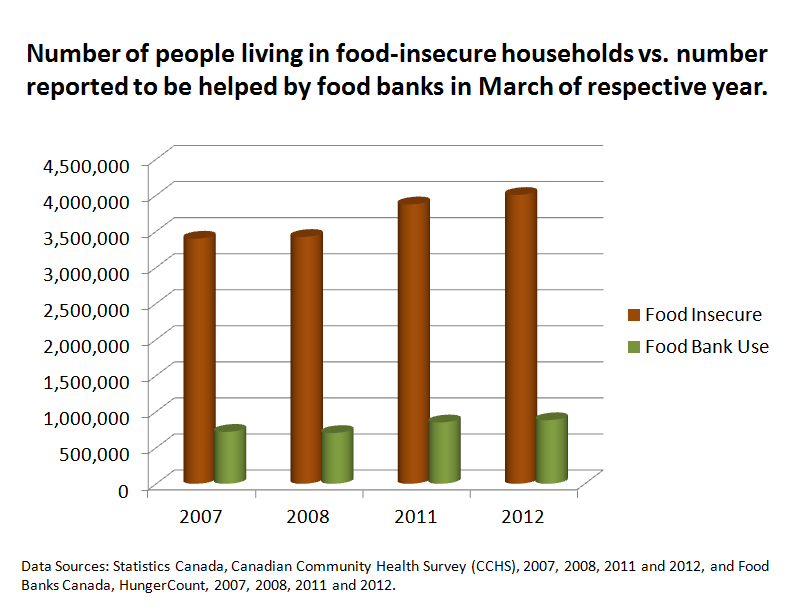

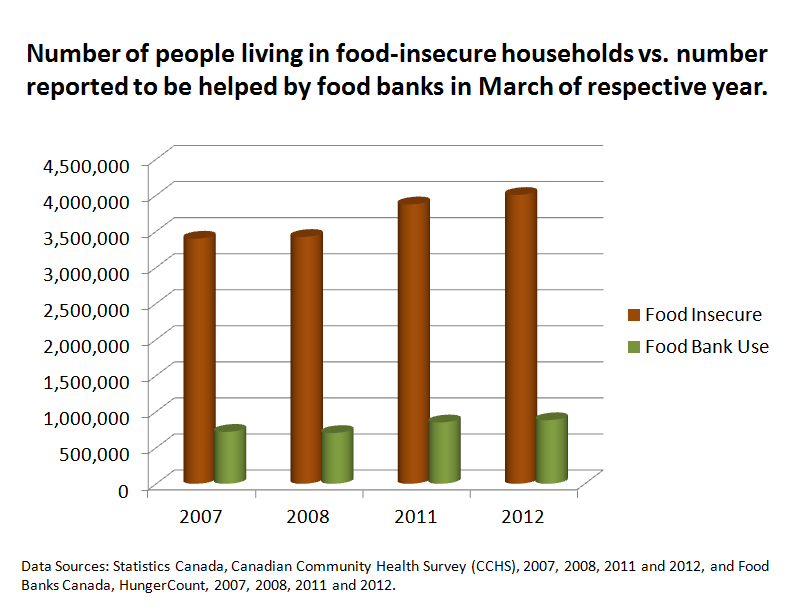

Food bank stats significantly understate the prevalence of food insecurity. We know this because Statistics Canada has been monitoring the problem nationally for almost a decade through the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). With its rigorous methods and large sample size this survey provides reliable health data at the provincial, territorial and national levels. It reveals more than four million Canadians were food insecure in 2012 — the most recent national estimate we have.

Food Banks Canada surveys its members every March to estimate use. In 2012 they estimated that only 882,188 people used food banks that month. The stark difference between the results of the CCHS and Food Banks Canada shows there’s a much larger problem than we’ve understood. Food insecurity in Canada is a national crisis.

Food bank stats also fail to capture changes in food insecurity over time. While the Hunger Count report draws attention to annual differences in food bank use in each province, food bank use actually appears relatively stable over time in comparison to the trends in food insecurity revealed by population stats. From 2007 to 2011 for example, we saw a steady decline in food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, and a steady increase in Nova Scotia. But neither trend could be seen in food bank statistics.

“Many felt visiting a food bank wasn’t something a ‘person like them’ they should be doing.”

Our research group’s study on low income families in Toronto found almost all of those surveyed experienced food insecurity, yet only 23 percent actually used food banks. When we asked ‘why?’ it became clear there was a disconnect between how families thought about their actual needs, and what services the food banks were offering.

Many felt visiting a food bank wasn’t something a ‘person like them’ they should be doing, or something that could help them out of their situation. By the time families are food insecure they face much more than a lack of food. They are likely behind on bill payments, rent and other basic necessities. If they are also dealing with chronic illness, they may be foregoing critical expenses like medication too.

Turning to a food bank for help was an act of desperation. But even with this assistance, most families remained food insecure. This finding is consistent with other research in Canada — showing it takes substantial improvements to a household’s financial circumstances, to shift them out of food insecurity.

Food bank stats are a poor barometer of food insecurity because they don’t describe the size of the problem or how it’s changing over time. On the other hand the CCHS allows us to accurately measure the extent of food insecurity and systemically investigate its causes and consequences. Since we began monitoring, we’ve learned food insecurity is a serious public health issue that impacts physical, mental and social health — and healthcare costs, too.

“Even with this assistance, most families remained food insecure.”

We also have a growing body of evidence showing the prevalence of food insecurity is responsive to changes in social policies. Yet there have been no public policies introduced so far, with the explicit goal of reducing food insecurity. We must shift the conversation from food banks toward insights from population stats, and upstream approaches to address food insecurity in Canada.

Commentary | Story

Food bank stats don’t tell the story of food insecurity

March 3, 2016

This article on the need to shift away from food bank statistics for discussing food insecurity was written for Upstream‘s series focused on food insecurity in Canada.

‘Food insecurity’ refers to the inadequate access to food because of financial constraints — and it’s a larger problem in Canada than most realize.

Since 1997 Food Banks Canada has released annual reports called ‘Hunger Count’ documenting the food bank usage. These reports have received wide media attention and are now a common point of reference when we discuss Canadian food insecurity, but they barely scratch the surface of the problem.

Food bank stats significantly understate the prevalence of food insecurity. We know this because Statistics Canada has been monitoring the problem nationally for almost a decade through the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). With its rigorous methods and large sample size this survey provides reliable health data at the provincial, territorial and national levels. It reveals more than four million Canadians were food insecure in 2012 — the most recent national estimate we have.

Food Banks Canada surveys its members every March to estimate use. In 2012 they estimated that only 882,188 people used food banks that month. The stark difference between the results of the CCHS and Food Banks Canada shows there’s a much larger problem than we’ve understood. Food insecurity in Canada is a national crisis.

Food bank stats also fail to capture changes in food insecurity over time. While the Hunger Count report draws attention to annual differences in food bank use in each province, food bank use actually appears relatively stable over time in comparison to the trends in food insecurity revealed by population stats. From 2007 to 2011 for example, we saw a steady decline in food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, and a steady increase in Nova Scotia. But neither trend could be seen in food bank statistics.

Our research group’s study on low income families in Toronto found almost all of those surveyed experienced food insecurity, yet only 23 percent actually used food banks. When we asked ‘why?’ it became clear there was a disconnect between how families thought about their actual needs, and what services the food banks were offering.

Many felt visiting a food bank wasn’t something a ‘person like them’ they should be doing, or something that could help them out of their situation. By the time families are food insecure they face much more than a lack of food. They are likely behind on bill payments, rent and other basic necessities. If they are also dealing with chronic illness, they may be foregoing critical expenses like medication too.

Turning to a food bank for help was an act of desperation. But even with this assistance, most families remained food insecure. This finding is consistent with other research in Canada — showing it takes substantial improvements to a household’s financial circumstances, to shift them out of food insecurity.

Food bank stats are a poor barometer of food insecurity because they don’t describe the size of the problem or how it’s changing over time. On the other hand the CCHS allows us to accurately measure the extent of food insecurity and systemically investigate its causes and consequences. Since we began monitoring, we’ve learned food insecurity is a serious public health issue that impacts physical, mental and social health — and healthcare costs, too.

We also have a growing body of evidence showing the prevalence of food insecurity is responsive to changes in social policies. Yet there have been no public policies introduced so far, with the explicit goal of reducing food insecurity. We must shift the conversation from food banks toward insights from population stats, and upstream approaches to address food insecurity in Canada.